All research and commentary by Jefferson Hall

Duels and the City Pound… The Rogers House and the story of the “twin daughters”… Was the Pink House always Pink? Did Sherman have a girlfriend? Did Washington really visit the Eppinger House? How many squares did Oglethorpe intend? Why do some of the squares have moss while others do not? What was the strange building by today’s Cultural Arts Center? And while we’re here let’s clean up some misconceptions about old Ft. Wayne and the DeBrahm Map, too…. Stories swirl around Savannah’s history and too often go unquestioned. Time to bust some myths!

Popular lore: The City Pound, south of the cemetery, was where duels were sometimes fought.

The reality: Only if duels were fought by cows.

Despite all the lore, there is no recorded instance of any duel ever being fought on the City Pound, and frankly, neither the timing nor the location would have made a (cow)lick of sense. The City Pound was exactly what the name would suggest… it was an impound lot where recovered stray animals were kept and auctioned off. It was a public lock-up for lost or misplaced horses, goats and mostly cows.

The City Pound arose out of an April, 1810 ordinance which made it illegal for large animals to roam the streets free. Owners of cows, horses and goats were expected to keep their animals on premises and were to be subject to seizures and fines of their animals if caught by authorities. Confiscated animals would be repeatedly listed in the newspapers; if unclaimed after a certain period they were sold at public auction on the same Pound lot. In an 1817 advertisement the City Pound had been located on Lot 23 of Franklin Ward, but by the time it next appears in advertisements in 1824, the Pound had moved to its current location south of the Cemetery, where it remained an active impound lot for loose animals for the next seven decades. The last recorded sale was a “fine draft horse” on August 1, 1896. On October 9, 1896 the City Council formally turned the City Pound into a park. From the Proceedings: “Be it ordained… that the tract or parcel of land in the City of Savannah, known as the city pound lot, now adjoining Colonial park to the south… is hereby dedicated to park purposes.”

There was a stable and tenement on premises; a 1852 Savannah Daily Republican made reference to “a stable attached to the city pound, near the old cemetery.” The 1853 Edward Vincent Map depicts the stables and other structures on the Pound lot.

Four years later, in a September 1, 1856 news item the Republican recorded the tenement’s destruction by fire.

So there was an attendant and caregivers on premises; it wasn’t a secluded spot even in the 1820s, and given all the manure any “duelist” surely would have had to have watched their step if taking paces. Also, by the time this lot had become the City Pound dueling had long been outlawed, and given that it was city property, such would not have been looked upon favorably.

This was not a site where honor was decided; it was where cows pooped.

Popular lore: This is the Eppinger McIntosh House, where George Washington stayed.

The reality: It is the Eppinger House… probably nothing else above is correct.

The property standing at today’s 110 East Oglethorpe was not McIntosh’s house. Lachlan McIntosh (1727-1806) lived and died in Heathcote Ward on Barnard Street. As far as I can tell McIntosh never had anything to do with this property; the house remained within the Eppinger family until after McIntosh’s death.

Nor can I find no evidence that this property was visited by Washington during his 1791 visit. To be clear, the house did exist then; the lower two levels of the property likely predate 1784, so it’s not impossible… but the fact that it is one of the few properties still existing from the time of Washington’s visit it does not necessarily follow that he did. A colloquial family legend maintained Washington visited McIntosh’s house, but if this wasn’t McIntosh’s house then it is hard to reconcile this property as the site.

I blame this 1919 plaque on the house, misinforming people for a century and counting. Not a claim on this marker seems correct. Washington stayed at Brown’s Coffee House on today’s Telfair Square, not here. The “Long Room” in question was in the Filature on Reynolds Square, not here. And McIntosh did not live here at any point between “1782 and 1806.”

Despite later Eppinger family legends, referring to the house as “Eppinger’s Tavern,” and claiming “the extent to which it became part of Savannah’s social scene can be judged by the newspaper advertisements of the period” (https://www.savannahga.gov/DocumentCenter/View/18576/1121-073_Anson_acc [page 55]), there is not a single advertisement or reference to any “Eppinger Tavern” in any Savannah newspaper between 1763 and 1810, and there is no reference to the Eppinger House at all before 1799, when it hosted a dance class of Mr. Francis, and again in 1802, when James Eppinger offered a room in the house for rent.

More on this topic may be found in the post on Washington’s visit to Savannah.

Popular lore: The Charles Rogers House on Monterey Square was built for his two competitive daughters (or twin daughters [story variant])

The reality: So silly.

Bluntly, this was just pulled out of someone’s arse; I mean, there are numerous duplexes in town; why this one is saddled with such a silly story and not every other duplex in town is a mystery. (Or how about a row house and competing quintuplets?)

Presbyterian minister Charles Rogers owned multiple properties downtown. He obtained the full lot that would become his dwelling in 1858, yet like so many other property owners, he did not require the entire lot. Rogers had not two but three children—one son and two daughters (no twins). Did either of the daughters ever own one of the properties? Well, yes… one did, after everyone else was dead. Charles died in May of 1861, and the northern half of the duplex was ultimately sold to Algernon Hartridge in 1862. Younger daughter Caroline had already married into the Stiles family but died in 1863; Widow Caroline left the southern half to sole surviving child Anna in her will as of 1885, and Anna died the following year.

Popular lore: The Old Pink House was built in 1771 and has always been… pink.

The reality: It’s a little complicated. The structure dates to about 1789 and has only demonstrably been pink since the early 20th century.

The lot in question was purchased by James Habersham, Jr.(1745-1799), on September 7, 1771; I’ve seen a copy of the deed, and there were already frame structures on the site, so the house that we see today came about some years later. Litigation initiated by Joseph Clay concerning the property in 1789 would suggest that the house we see today was begun in or just before 1789.

Undated article by Mary Rolls Dockstader in the Southern Architect and Building News:

“It appears that James Habersham, Jr., did not immediately build on this property. At the time of building the house, the records show that Joseph Clay built it and financed it for James Habersham and that up to 1789 no brick buildings stood on the lot, but there is evidence of some frame structures. Mr. Habersham evidently built beyond his means as the court records tell. Clay levied on the east half of the lot and the brick building thereon in 1789. So it is well established that this house was not actually built until shortly before 1789.”

Retired attorney Shelby Myrick to Walter Charlton Hartridge, January 28, 1965:

“With reference to the Pink House in my statement that it was not pink when I had an office there from 1897 to about 1906 or 1907, I still have the distinct impression that the building was a very light brown. The garden was enclosed in walls, and I am positive they were not pink on the outside. I never heard this building referred to as the ‘Pink House’ until the last few years.”

Interesting tidbit: In 1927—with the demolition of the Pink House a very real prospect that year—the Lane family created a replica of the Habersham House across the street from their home on Gaston Street; standing today at the northeast corner of Drayton and Gaston Streets, this “Gray House” at 102 East Gaston represents the Pink House’s original design, before its 1812 northern addition.

Popular lore: Sherman didn’t burn Savannah because of some old girlfriend or acquaintance.

The reality: No.

Sherman was a pragmatist. While Sherman had visited Savannah back in 1840, no… he had no girlfriend here and few acquaintances. Sherman’s behavior towards Savannah reflected his pragmatism. Simply, there was simply no strategic value in burning Savannah. Atlanta, of course, was a town of major strategic, industrial and manufacturing value—only Richmond turned out more war-time materials for the Confederacy than Atlanta. Savannah, however, held no such strategic value—even as a port Savannah had already been effectively blockaded with the taking of Fort Pulaski two-and-a-half years before, and Sherman’s army completed the job by taking Fort McAllister in December, 1864. Sherman’s stated intention as early as December 24, 1864—his second day in Savannah—was to leave a garrison behind. Savannah was to be an occupied town. As Sherman wrote to Grant on December 24, 1864:

“I feel no doubt whatever as to our future plans. I have thought them over so long and well that they appear as clear as daylight…. I will have to leave in Savannah a garrison, and if Thomas can spare them, I would like to have all detachments, convalescents, etc., belonging to these four corps, sent forward at once.”

On January 4, Admiral John Dahlgren remarked in a letter to Gideon Welles, the Secretary of the Navy, that “since the occupation of the city General Sherman has been making arrangements for its security after he leaves it for the march he meditates.”

On January 18 General John Gray Foster officially took over control of the Savannah garrison as Sherman resumed his march.

Popular lore: Oglethorpe had the foresight to lay out Savannah with 24 squares in a grid, and intended the squares as parks.

The reality: Oglethorpe never designed, intended, or even imagined the need for more than six… and parks were not really on his mind.

Really, Oglethorpe laid out just the one square (Johnson), the others simply followed the template of the first. While Oglethorpe himself never explained the purpose or inspiration for the squares, to him a square seems to have been intended as empty space, a conclusion suggested in the Journal of William Stephens, as Oglethorpe put the colonists to work in 1739, removing the growth that had appeared within during his absence.

“The General observing, that since the Land of the Common being cleared of Trees, Abundance of Shrub-Wood was daily growing up, which filled the Ground; and that the publick Squares, and most open Parts of Town, were filled with an offensive Weed, near as high as a Man’s Shoulders, both which were a great Annoyance, and… harboured and increased many troublesome Insects and Vermin; and moreover, if set on Fire when dry, might endanger the Burning of the Town. For these Reasons he was pleased over Night to send out Orders, that upon the Beat of Drum this Morning, all Persons inhabiting the Town… should appear at Sun-rising this Morning, and go to Work clearing this great Nuisance: Which accordingly they readily did.”

– Colonial Records of Georgia, vol. IV, p. 433

So exactly why did he intend his squares to be empty spaces? It’s important to consider one small detail in above account that might help address this question. Stephens remarked—and it is easy to infer that the following was based on Oglethorpe’s own words—that the growth in question not only “harboured and increased many troublesome Insects,” but “moreover if set on Fire when dry, might endanger the Burning of the Town.” This seemingly-throwaway, secondary-sourced comment offers us a crucial insight: As a man born a generation after the Great London Fire, Oglethorpe was not oblivious to the damage fire could wreak on a town; the above suggests that fire-prevention was one of Oglethorpe’s conscious and deliberate reasons for Savannah’s open spaces.

Speaking of the squares, I used to get this one a LOT as a tour guide….

Question: “Why does [fill in the blank] Square not have any moss?”

Popular lore: Ghosts!

The reality: Park and Tree Department.

Certainly spookier than any ghostly entity, the City of Savannah is to blame for such an unnatural inequity. Listen, as an alumnus of the Savannah College of Art and Design I can recall well (and can offer artistic proof) that Reynolds Square had Spanish moss in abundance in 1989, as I illustrated the negative space and could barely discern the John Wesley statue from the hanging moss around it. Sometime thereafter, though, the City made a deliberate decision to clear all squares north of Oglethorpe Avenue (aka, the business district). John Wesley has not seen moss in decades. Simply, today one will not find Spanish moss in any of the eleven squares north of Oglethorpe Avenue… a result less based on spectral activity than on economics; the stuff gets everywhere and is still often regarded as a nuisance. Sure, Spanish moss may be seen by some as majestic, mysterious and haunting, but it also may be regarded as messy and an unpleasant find on one’s windshield after shopping. It may change in the future, but for now, Oglethorpe Avenue is the dividing line between a square with moss and… not.

Question: So, wait… what exactly IS this thing?

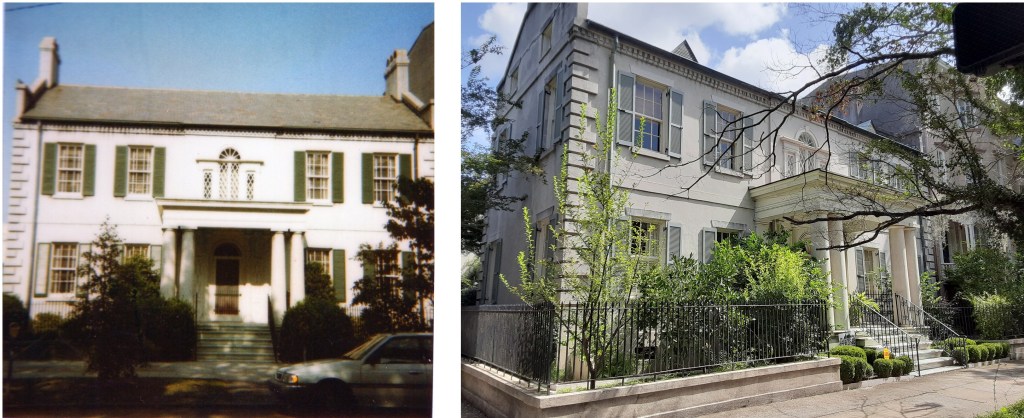

The reality: Not appearing on maps before 1898, this was an outbuilding belonging to the Augustus Wetter House.

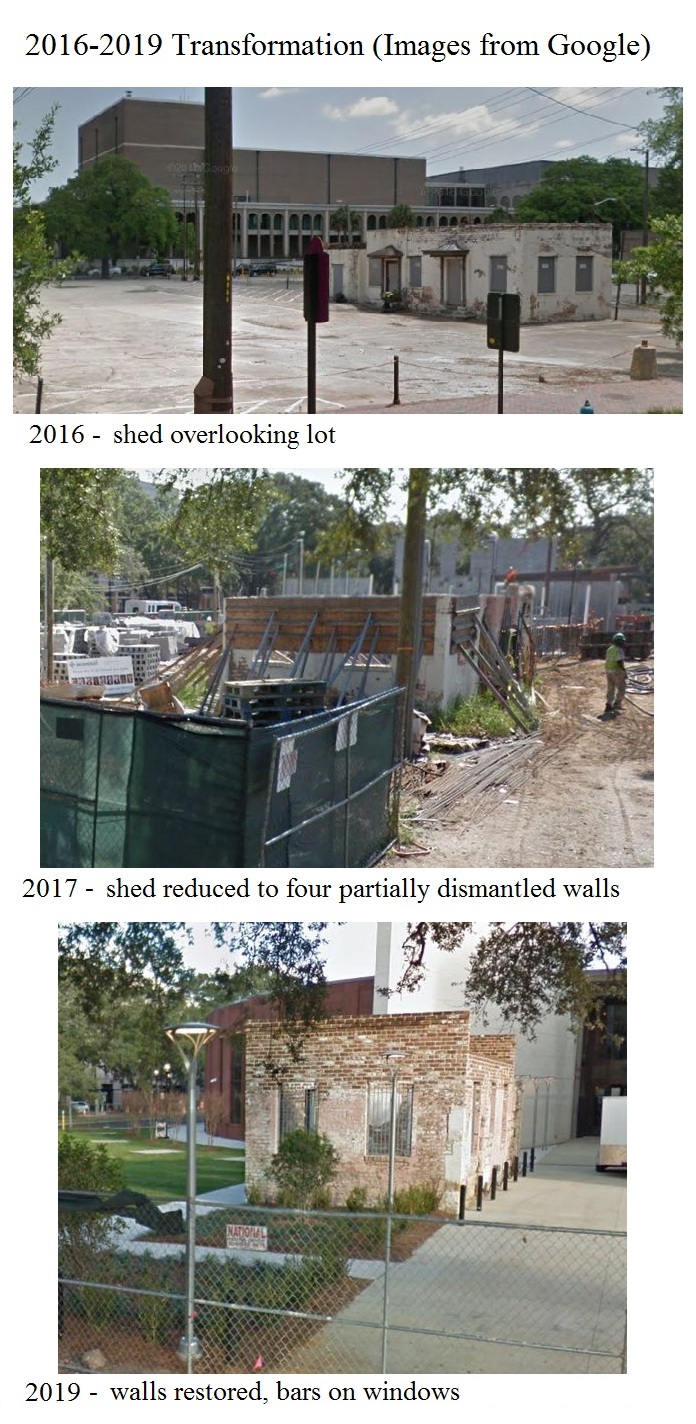

Near the corner of Oglethorpe Avenue and Martin Luther King Blvd, tucked away within the compound of the 2019 Cultural Arts Center, stands a rather odd and mysterious, hollowed-out structure. Its barred windows alone beg questions… was this some old 18th century jail? It looks imposing and stirs the imagination… but honestly, the reality is a bit underwhelming. The bars were added to the windows in 2019(!), and the structure first appears on the 1898 Sanborn Insurance Map, an outbuilding simply described as “shed.” Bluntly, its value today is derived from the fact that it is last remaining vestige of one of the most lamented demolitions of the 20th century… even if this fruit fell rather far from the tree.

The Augustus Wetter House appears to have had its beginnings in or about 1822, but it was in 1857 that the house began to assume the more iconic appearance found in surviving images today. Built at the corner of South Broad (today Oglethorpe) and West Broad (today MLK) the house remains one of the lost treasures of Savannah, though its distinctive balcony fence-work survived and may still be found around town at Chippewa Square or around the gryphon statue at the Cotton Exchange. Having previously occupied sites on Greene Square and Madison Square, by 1891 the Savannah Female Orphanage purchased the property, remaining in possession of the lot until 1950, at which point the lot was bought by a Chevrolet dealership. The house was demolished, and until 2016 all that remained on the empty, former car lot was the old outbuilding at the back used in the day as a sales office.

In the 2010s, as plans developed to build the Cultural Arts Center, it was decided to save the one remaining 19th century structure on the lot, while also restoring it as closely as could be ascertained to its original configuration. This entailed reducing it to its 19th century footprint and resorting to Sanborns to determine its original size.

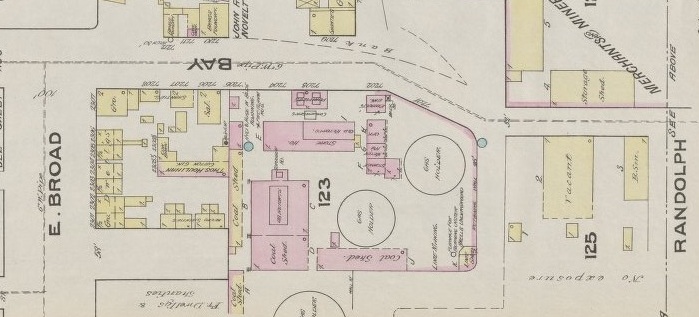

In considering the Sanborn Maps it is important to note some factors upfront. These were fire insurance maps and were intended to accurately reflect every property extant on any particular lot. The first of these maps was published in 1884; these were not yearly publications, instead the next followed in 1888 and thereafter, 1898. Using these tools is a rather imprecise tool for dating properties, but the shed—not visible in 1884 or 1888—was clearly extant by 1898 and again in the 1916. One will note in the figure the considerable improvements made to the lot between the gap of 1888 and 1898, this followed the purchase of the lot by the Savannah Female Orphanage in 1891. This suggests the shed likely did not predate the Orphanage but was probably erected early in its tenure, during the period between 1891 and 1898. One might also note that the shed was built into the older compound wall enclosing the lot, resulting in the fact that its southern wall features different construction materials. Facing the lane, this wall was far less polished than the sides facing South and west Broad Streets.

Today the building stands as a curio, a somewhat ill-defined and austere structure sitting in the shadow of the more avant garde Cultural Arts Center, but the structure’s history is a bit… underwhelmingly utilitarian.

Popular lore: The walls visible from General Macintosh Blvd are remnants of Ft. Wayne.

The reality: But it had no walls… Fort Wayne (versions 1 and 2) was entirely an earthen-works structure; the walls we see today were from the Gas Works compound, and post-date 1853.

Back in the 1990s I frequently rode my bike to the old Pirates’s House/Trustees’ Garden/Fort Wayne neighborhood. Tucked away at the wall’s edge there existed at the time a small retinue of four or five non-historical houses—the Hillyer Compound, a mid-20th century residential development of Mary Hillyer. Perhaps better known as Trustees’ Garden Village, it was a tiny, self-contained cul-de-sac enjoying a lovely eastern view over the wall. Rusted cannons were perched over the precipice, facing east as though poised to combat some equally rusted enemy. In walking these “battlements” one could see an opening in the ground near the south-east corner of the wall, an unexpected “downstairs,” if you will, which led to a ground-level exit through the wall’s only external archway. Though the access to the opening in the ground was fenced off and unapproachable I would often crane my neck to better view what we all believed was the old powder works or some secret entrance to whatever remained of the fort beneath. One day while I was visiting and participating in this practice, a stranger appeared beside me. “It’s a nice view, isn’t it?” he asked, as we watched the cars on General McIntosh Blvd go about their business. I agreed, and our conversation continued for a few minutes before he politely concluded: “You know, this is private property.”

Terribly embarrassed, I never again set foot on the compound of the Trustees’ Garden Village. A few years later the houses were removed; today not a trace of the Hillyer Compound remains, even aerial views reveal not a hint… an example of how quickly and entirely the topography—Savannah in general, but more specifically, the old fort hill—can alter without a trace. Even those old cannons are gone, eventually re-homed at Fort Jackson.

It is safe to say that nothing of the old Fort Wayne remains today. But ironically, even as I rode my bike there in the 1990s nothing had remained, though the cannons and the lower archway had me believing otherwise. What I had then assumed a powder magazine or secret entrance is found identified on the 1884 Sanborn Map as simply a “lime shed” next to the “Furnace for burning oyster shells underground,” all part of the later Gas Works. The reality is that Fort Wayne was never brick, and though the cannons were genuine, they were found there, buried relics uncovered during the 1850 excavation and later staged on the subsequent Gas Works walls. Alas, nothing is as it seems. So let’s dive in with a brief history of Ft. Wayne and the Gas Works.

The late 18th century Ft. Wayne fortifications were earthen-work and timber; this old fort area was ceded to the federal government upon a petition by George Jones on January 12, 1808, following a request by the US Secretary of War. Though no renovation work was undertaken right away, City Council resolved on June 19, 1812 (ironically, the same day that war was declared, though no one knew it at the time) that “it is deemed expedient immediately to commence the rebuilding of Ft. Wayne.” While not depicted on an 1812 city map, “Ft. Wayne 2.0”—that is to say, the Ft. Wayne of the 19th century—makes its first appearance by the 1813 Map. GHS Collection #1018 contains a beautiful c.1821 surveyor’s depiction. A very fluid design, erected between 1812 and 1814, entirely earthen-works platforms, this “Fort Wayne 2.0” appears on a handful of maps over the next several years until gradually fading away through neglect. A barracks, which had been built a few hundred feet to the south, was active until the mid-1820s, but ultimately replaced by the Oglethorpe Barracks on Liberty Street in the 1830s.

Fort Wayne had effectively ceased to exist by the 1842 Stephens map; Charles Olmstead (1837-1926) recalled from childhood that beyond East Broad Street was “a grassy slope, (site of the Trustees’s Garden in Colonial times) and the remains of an old earth-work erected, I believe, during the War of 1812.” Really, by November of 1839, the Daily Republican rejoiced that what remnants of the old fort still existed were being graded into Reynolds Street.

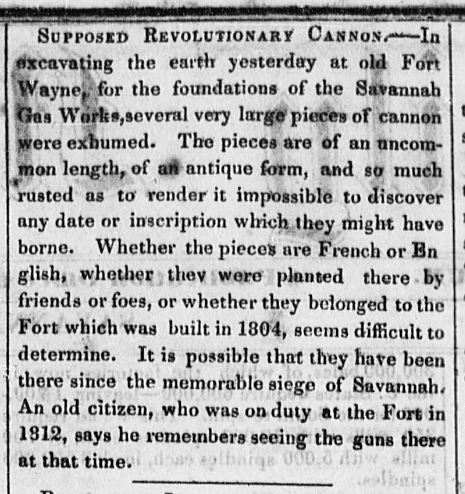

A decade later, by January of 1850, the Savannah Gas Light Company was created and, following brief negotiations with the Federal government officially purchased the property. In March leveling of the remaining slopes began. The March 15 Morning News remarked that workers were “excavating the earth yesterday at old Fort Wayne, for the foundations of the Savannah Gas Works.” It was during the excavations that they uncovered a surprise. As the March 15 Republican noted: “Three large iron guns, stated to be 32 pounders, were disentered at the old Fort yesterday, while excavating for the foundations of the gas works.” Thus marked the origin of the old orphaned cannons which would eventually find their way atop the walls of the Gas Works.

By April 5 the Morning News remarked of the progress on the east end of town: “The old Fort is rapidly undergoing a change, and in a few days the old Magazine will also disappear.” The following week the Republican boasted of “the metamorphosis of the old fort,” with buildings being erected and gas complex compound taking shape. “There, all old things are being done away, and all things are fast becoming new.” By July the bulk of the new compound had been completed.

So does that mean the outer walls we see today date to 1850? Well, not exactly. In discussing the new Gas Works compound, the July 20, 1850 Republican observed that it was to be bounded on the east side by an artificial wall of green sods… in other words, more earthworks. The 1853 Vincent Map offers us the oldest glimpse of the gas company’s complex and depicts the new slope wall.

Often referred to thereafter as “Gas House Hill,” the property was next illustrated in the 1871 Birdseye View of Savannah. By this time it had clearly delineated outer walls. In short, not only do the walls we see today not date back to Ft. Wayne, but they don’t even date to the earliest iteration of the Gas Works compound.

The Savannah Gas Light Company enjoyed a monopoly in Savannah until 1884 and continued to incrementally alter, enlarge and improve the compound between the 1850s and the 1890s, but the last vestiges of tiny Ft. Wayne had been long cleared away. The March 14, 1850 Morning News reported that “150 men” were “employed in removing the earth, and laying the foundation of the buildings.” To be blunt, much like the Hillyer Compound cul-de-sac I would encounter on the same site in the 1990s, by 1850 Ft. Wayne was reduced to a memory.

Popular lore: The DeBrahm Map to the right dates to 1757.

The reality: It appears to correspond to 1771 and emerged from a manuscript he penned in the 1770s.

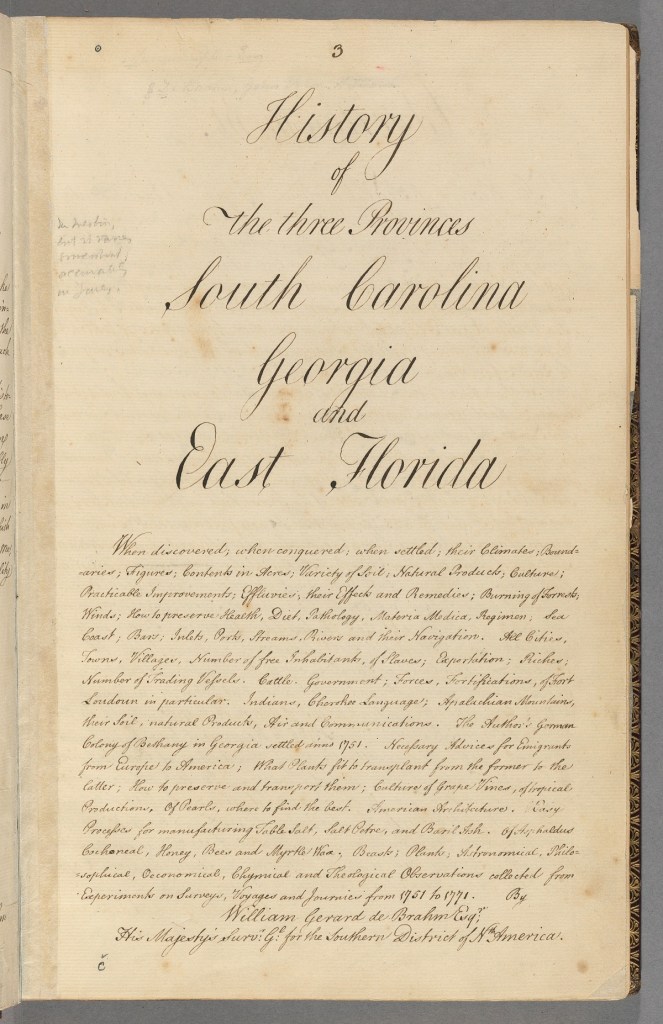

Anyone who has ever done a deep dive into Savannah history has encountered this familiar illustration. Known informally among many of us as “the DeBrahm Map,” its formal title is “Plan of the City Savannah and Fortification,” and it depicts the town in overhead and profile views, both featured on the same leaf. But really, what you’ve seen is a copy—either the copy produced by the Wormsloe Press in 1849, or a copy made from that copy. Every iteration we have of the map today derived from one original 18th century source, which came to light in 1848. Below is the original of our “Plan of the City Savannah and Fortification,” by John Gerar William DeBrahm. A unique item, it is located in the Houghton Library at Harvard and housed within the collection of the Colonial North American Project at Harvard University.

The illustration accompanied DeBrahm’s hand-written manuscript, History of the Three Provinces: South Carolina, Georgia and East Florida, an enormous folio containing his two decades of research between 1751 and 1771, and addressed on its opening page “To the King’s Most Excellent Majesty,” King George III. The seventeen-chapter, three-volume work represented his final report and the end of DeBrahm’s tenure as surveyor. With many of its graphs, figures and annual tables terminating at 1771, the report was current to his departure from the New World. Although there is no precise year of authorship attributed to the manuscript, it is evident the manuscript was brought to completion between 1771 and 1773. For example, within the Appendix of the manuscript (pages 343-44), while discussing the “foregoing seventeen Chapters… of the three Provinces,” DeBrahm referred to 1763 being “just ten years ago,” and one of the tables in the manuscript’s Florida volume is visibly dated to 1773 (page 261). Prudently, Harvard’s own current citation dates the manuscript to simply “after 1771”.

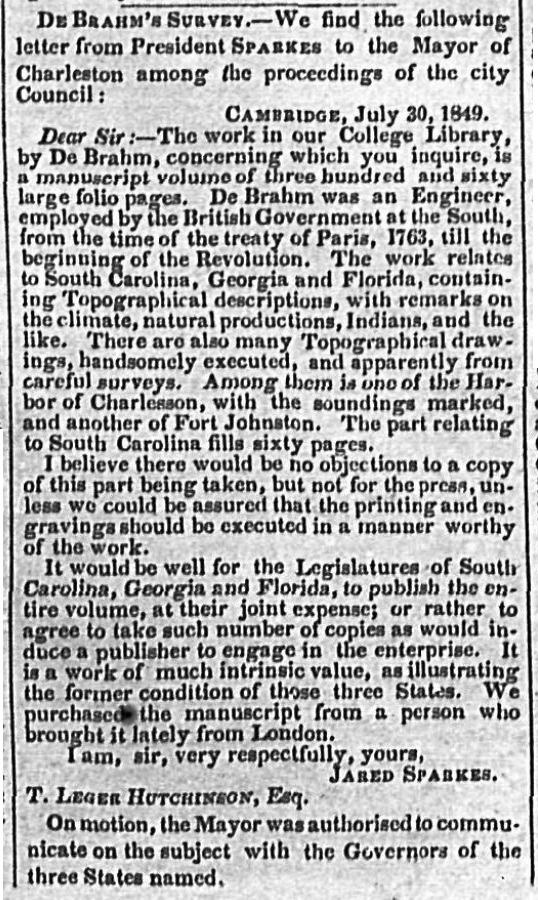

Soon after the manuscript was acquired by Harvard in 1848; relevant parties were made aware of its existence. In the summer of 1849 the mayor of Charleston inquired of Harvard President Jared Sparks, whose reply was published in the Savannah Daily Republican on August 11, 1849:

It seems that George Wymberly Jones (later George W. Jones DeRenne) was unwilling to wait for coordination among various legislatures; later in 1849 he produced a copy of the Georgia volume (excluding the South Carolina and Florida volumes), printing the History of the Province of Georgia as a standalone publication (one might notice even in the above images the faded pencil notes as to what Jones was copying). Not to be left out, in South Carolina Plowden Weston did the same for the South Carolina volume. Published by his Wormsloe Press as a limited edition of 49 copies, Jones’ version faithfully transcribed the text and recreated the illustrations from the original manuscript, with the “Plan of the City Savannah and Fortification” suffering only an occasional typographical/transcribing error (i.e. – “Indept. Meeting” was mis-transcribed as “Indian Meeting” and the original’s “Basilica” references became “Basilua” [As a frustrated later correspondent remarked in the December 2, 1900 Morning News: “I can find no such word in the dictionaries, and must plead ignorance as to what the map maker meant.”]). Typographical errors notwithstanding, it was Jones’ 1849 publication of the History of the Province of Georgia that reintroduced DeBrahm to Savannah and brought to light his illustration of the “Plan of the City Savannah and Fortification.”

But where did the attribution of 1757 come from if the illustration in question is undated? The Savannah Morning News articles of April 23, 1899, June 4, 1899, December 2, 1900 and June 2, 1902 cited 1757 as the date, and in trying to understand the assumption there are potential reasons for this.

Arguments FOR 1757

- In 1757 DeBrahm published his definitive “A Map of South Carolina and a Part of Georgia, Containing the Whole Sea-Coast,” which is the map to the right… and clearly dated 1757. This survey was updated and reprinted in 1780, and regarded as so authoritative that it even played a role in settling a property dispute between South Carolina and Georgia in a 1990 US Supreme Court case. As his most famous cartographic work, to the world outside of Savannah, this was (and is) “the DeBrahm Map.”

But this 1757 map does not include—and should not be confused with—the “Plan of the City Savannah and Fortification,” which does not seem to appear anywhere outside of the 1770s manuscript, and like the other graphs/tables/illustrations within the manuscript, seems current to his departure.

- In July of 1757, Georgia’s Colonial Legislature authorized the “Security and Defence of the Province by Erecting Forts in the Several Parts thereof” Act, in reaction to the French/Indian War; in short, 1757 marked the year that the colony was put on defensive footing. As DeBrahm wrote, “when the Author in 1757 returned… to Savannah” he was approached by Governor Ellis and Council regarding the creation of defensive works around the town, adding that “the Author’s Advice met with general approbation.” (History of the Three Provinces, pp. 124, 127)

The problem with this argument is that it’s not clear from the record what DeBrahm suggestions were implemented immediately and what were held off until 1760. In April of 1760 the Legislature authorized an “Act for… better securing the Town of Savannah by erecting a Fort round the Magazine and block Houses within the Lines of said Town.” (Colonial Records of Georgia, vol. 18, p.452) It is possible that the fortifications around Savannah—as illustrated—were not fully realized before 1760.

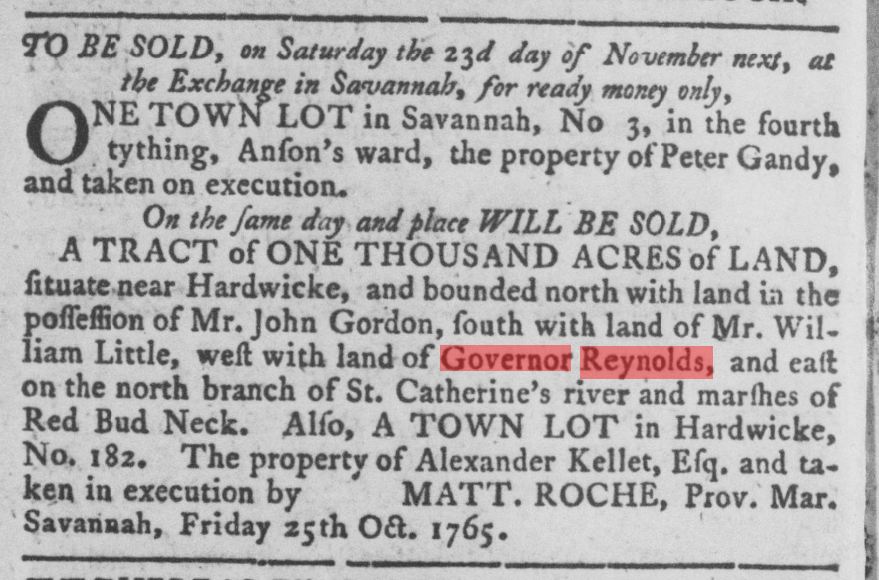

• The lot of John Reynolds is depicted intact; if Reynolds was only governor between 1754-1757 how could a lot be attributed to him after 1757?

The problem with this argument is that properties were still associated with him years after he left. The lot in question (Lot Z, Anson Ward) was granted in 1755; in a flurry of grants between 1755 and 1756 virtually all of the town’s public lots were granted to individuals (Colonial Records of Georgia, vol. 7, passim) as the Colonial government rejected the necessity for public lots. Whether Reynolds ever built on the lot is unclear; as seen to the left, DeBrahm himself was granted half of the neighboring Lot X in March of 1755, but by his own admission did not build on it before 1760 (History of the Three Provinces, p. 123). I cannot find any record of when Lot Z was relinquished, forfeited or sold to anyone else. Not to call out the 18th century elite, but all three of the Royal Governors were granted numerous Georgia properties during their respective tenures (Reynolds was granted 1.] “an Island containing Thirteen hundred Acres” 2.] “Five hundred Acres of Land in the district of Ogechee,” 3.] “Two Thousand Acres of Land situate between the Great Ogechee and Midway Rivers” in 1755, 4.] “Ten Acres to the Eastward of the Town of Savannah,” 5.] “Two Lotts in Hardwicke” and his aforementioned number 6.] “Lot in Savannah Letter Z” [Colonial Records of Georgia, vol. 7, p.283-84, 294, 312, 329]); when the governors eventually relinquished the properties is not always as clear as when granted. Consider the 1765 Georgia Gazette notice below; even eight years after Reynolds had left Georgia the Ogeechee land grant was still associated with “Governor Reynolds.”

Importantly, though… the “Plan of the City Savannah and Fortification,” also depicts a few features of the town that would not have existed in 1757:

Arguments for LATER

• Governor’s house – Long before the recognizable home of the Telfairs was built in Heathcote Ward, Lot N where today’s Telfair Academy stands had been occupied by the Governor’s house, the site where James Wright resided. But there was no official residence in 1757 Savannah; both Reynolds and successor Henry Ellis were determined to move Georgia’s seat of government to Hardwicke. It was Governor Wright who favored Savannah as the seat of government; a governor’s house in Savannah wasn’t even authorized by Georgia’s Colonial Legislature until 1760. On April 24, 1760, concluding that “it is highly expedient and Necessary that a proper and convenient dwelling-House should be provided” for the “Present and every future Governor,” the Legislature finally authorized a contract for one. (Colonial Records of Georgia, vol. 18, p.389) There was no governor’s house on Lot N in 1757.

• The Market is depicted in Ellis Square, a situation that did not occur before 1763 – The Market was created in 1755 (CRG vol. 13, p.63; also: CRG vol. 18, p.85), but in Derby Ward (Trust Lot B)… it was relocated to Wright Square “around TomoeChichichi’s burying Ground” by a September 18, 1759 act of Legislature. (CRG vol. 8, p.135) On December 10, 1762 the Legislature considered the motion to move it “to the Centre of Ellis Square” (CRG vol. 13, p.755). By February of 1764 the “Market Place and Buildings have lately been removed into Ellis Square;” the new market was nearly finished, “a further Sum… necessary for the compleating thereof.” (CRG vol. 18, p.572) Even so, a petition was presented in 1764 to return the Market to “the centre of the Town,” some folks finding its location “to one end thereof very inconvenient” (CRG vol. 14, p.88). The petition proved unfruitful, and Ellis Square would remain the host of the Market for the next 190 years. But to be clear: there was NO Market in Ellis Square before 1763-64.

• “Old Basilica”/“New Basilica” – This was a (slightly archaic) distinction between the old court house building and its replacement, and while “basilica” is not necessarily a term we associate today with court houses, it is not completely without historical precedent (feel free to google “court house basilica”). In February of 1764 the Legislature authorized a replacement for the 1736 court house building (CRG vol. 18, p.577-80); in 1766 a committee was formed and financial strategy implemented to raise funds for a new court house. The new court house was built on Lot F as Lot H was too congested (already Lewis Johnson’s petition to be granted the eastern half of Lot H had been rejected due to the presence of ancillary buildings of the court house on the back half of the lot [CRG vol. 7, p. 650]), meanwhile, the 1736 court house remained in tact with the intention of its sale to defray the cost of the new structure. In 1768 “One Hundred & fifty pounds” was paid “for Defraying the Expences of & Finishing” the replacement court house (CRG vol. 19, part 1, p.132). The committee overseeing the construction attended a meeting of the House on January 17, 1770 to report on the “state of their proceedings and Accounts” of the project (CRG vol. 15, pp.75, 91), and the Legislature reimbursed parties for construction costs in the 1773 Tax Act (which reimbursed expenditures back to 1770), suggesting the new court house was probably not completed before 1770. By 1772, the fledgling Lutheran congregation—whose members already had claims on Percival Ward’s Lot F and whose legacy grant of property by Rebecca Lloyd was contingent upon a house of worship being erected on the lot—purchased the 1736 court house building (for between 17 or 18 pounds, sources vary). Subsequently, the structures switched lots as the buildings were moved; the 1736 building was converted into the Lutheran Church and moved to Lot F, while the 1770 court house returned to its legacy Lot H. The DeBrahm Map makes no reference to the Lutheran meeting house—or the switch—but seems to correspond to the situation precisely as it would have existed in the window between c.1768 and c.1772.

So… 1757 or 1771 (…or some combination of both/neither)? DeBrahm’s “Plan of the City Savannah and Fortification” does display features that would seem to date the illustration later than 1757. The manuscript it accompanied—the only source for this image—was otherwise current to 1771-73. Might the image have been based on an earlier, original, c.1757 illustration? One might imagine it was based on many prior iterations of the same illustration, but ultimately the argument is rendered somewhat abstract if every existing copy we have came… from this one.

This is a fantastic web site and source. Jefferson has done a magnificent job of scholarly work. Thanks so much.

LikeLike