All research and commentary by Jefferson Hall

Let’s talk squares… or specifically, wards. So exactly what is a ward? How many did Oglethorpe lay out? How and when did all these wards come into being and shape the old town we admire today? Today’s city wasn’t so much Oglethorpe’s idea as some five generations of reinterpretation.

Popular lore: Oglethorpe designed all of the squares we see in Savannah today.

The reality: Well, Oglethorpe designed… one.

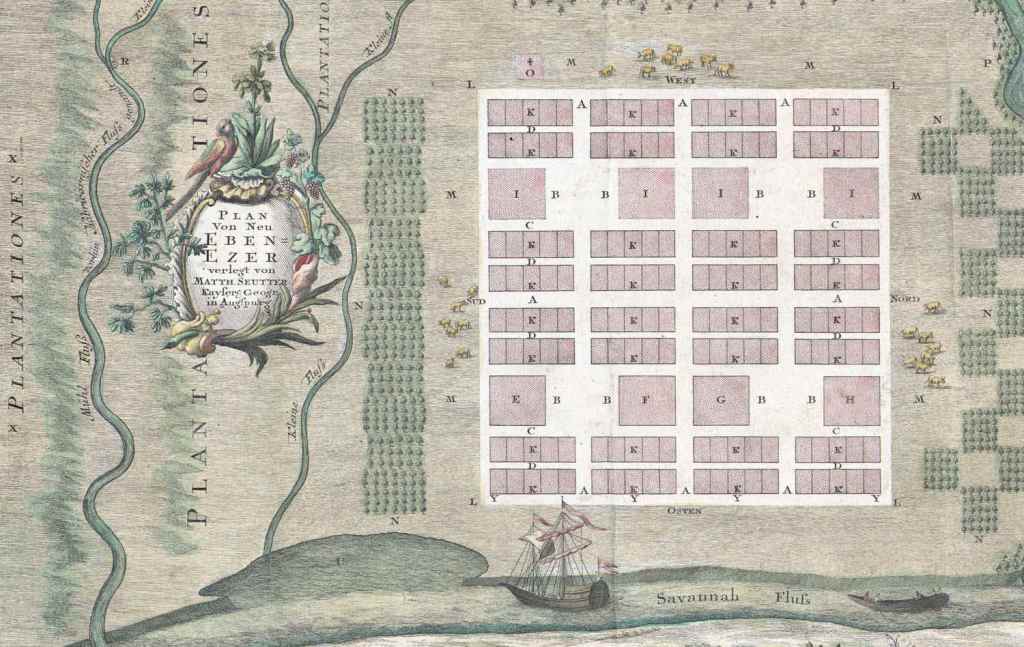

The design of Savannah’s layout is distinctive and one that has fascinated urban planners and any visitor for generations. Who doesn’t see the squares and wonder what Oglethorpe’s inspiration was? Where did this idea come from? Was it Robert Castell’s Villas of the Ancients, to which Oglethorpe’s name was affixed in the frontispiece as a subscriber/investor for two copies? Anyone looking for obvious answers will come away disappointed; the man never left any written record explaining influences that might have inspired his designs. And “designs” is indeed intended as plural in that Oglethorpe’s design for New Ebenezer, laid out in 1736, also featured a similar grid layout with squares…

So while Oglethorpe’s design might remain unexplained… it also remains unmistakable.

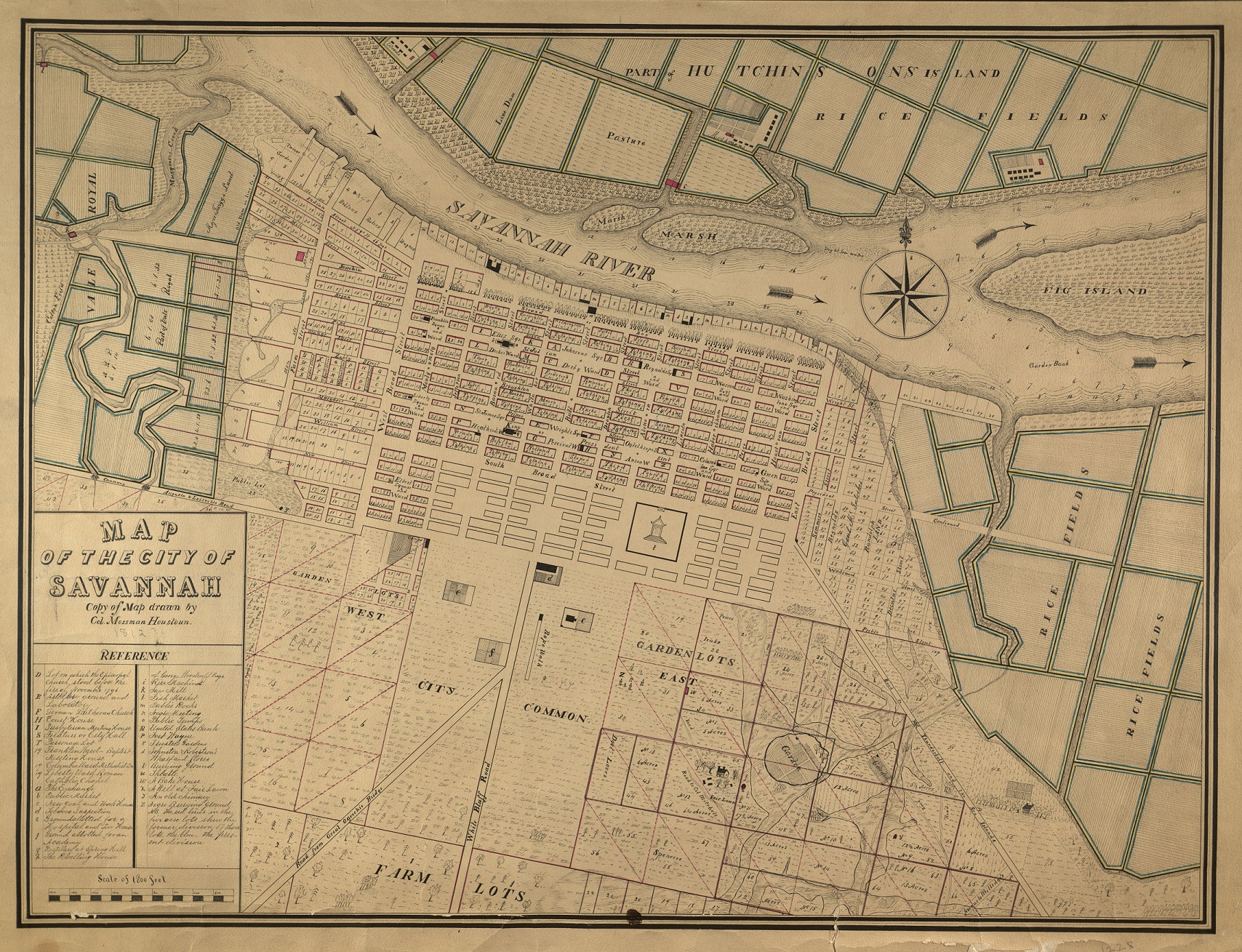

As can be seen in a separate post, Oglethorpe’s squares were never treated as parks at any point in the early decades; the square was basically the negative space to the ward’s positive space. Their evolution into parks came later… much later… like generations later. Nor did Oglethorpe conceive of 24 squares; to be blunt, the man was not mad. Put out of your mind any notion of a maniacal genius gripped by some vision of 24 squares, grabbing people by the collar exclaiming “24 and a park!” Instead, everything evolved organically. Oglethorpe laid out one ward, and eventually oversaw six… the Savannah that followed in his wake grew organically from these first six.

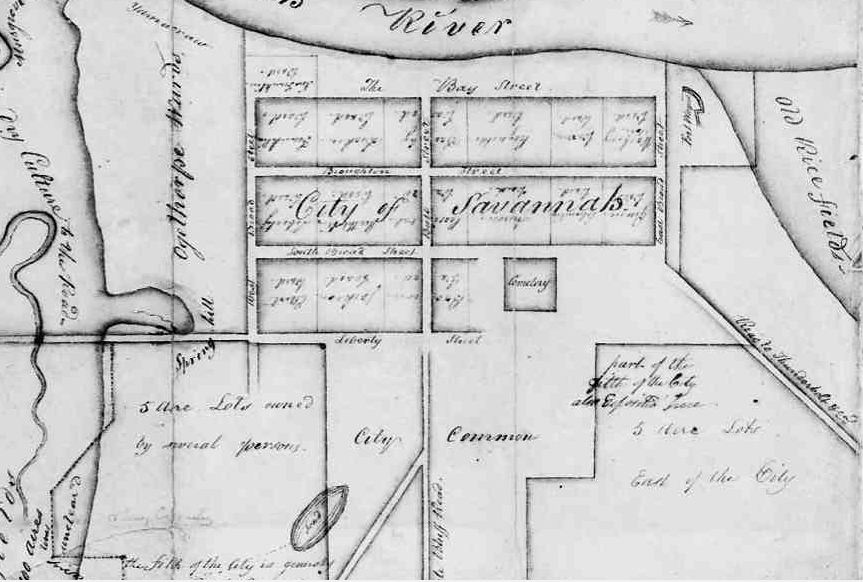

The “ward” was the building block of Oglethorpe’s plan… basically a contained design that could be copied and reused as a repeating template. He tailored the ward specifically around the embarkation he was accompanying across the Atlantic; there were 40 families aboard the Anne; accordingly, he laid out a template built around 40 house lots. Had there been 60 families aboard the Anne, I think we would be looking at a very different Savannah today.

The ward…

Oglethorpe designed a ward to consist of four tythings, four trust lots and an open space at the center. The tything lots to the north and south of the square would provide 10 house lots each, and though the trust lots were originally intended only for public buildings, this distinction was jettisoned by the 1750s. In 1753 various trust lots in Anson, Percival and Heathcote wards were granted as house lots; by 1755 the Governor and Council rejected the designation of the east-west public lots outright, concluding “that there were more Lots reserved for Publick uses in Savannah, than will probably ever be wanted for that Purpose.” (Colonial Records of Georgia, vol. VII, p. 107-8)

Despite our rather fanciful notion of Oglethorpe designing a city full of parks, the squares were initially unembellished empty spaces; they may have been designed as a bulwark against fires, if William Stephens’ interpretation of Oglethorpe’s words was correct (such an interpretation would also help to explain the width of the town’s streets… otherwise uncommonly wide for such an era). Over the decades, as houses and trust lots morphed and changed form, so too did the squares evolve and change, ultimately taking the appearance of public parks as we know them today.

Essentially, the City Common may be viewed as two dozen ringlets of ward neighborhoods… all representing different time periods, as early as 1733 and as late as 1851. So while it is easy to think of today’s Historic District as the fanciful imagination or execution of one man’s plan, it might be more accurate to compare it to the monumental realization of the massive, generation-spanning construction projects of Medieval Europe. No one in 1734 thought the town would spread farther to the south, just as no one in 1815 saw a walk to the poor house and hospital anything other than a trek through the wilderness or anyone by 1837 a cross from Liberty to the Oglethorpe Barracks or the old jail an adventure into the wiles south of town. In short, no generation had foresight beyond the next; to each generation their “Savannah” was complete and as fully realized as ours is today. As a surveyor of Oglethorpe’s time, Noble Jones had overseen the initial six wards… it was his middle-aged great-grandson who would witness the layout of the final three. The incremental filling of the City Common should be viewed as a sprawling monument spanning decades, adapting and changing as it was erected over the span of 120 years… or ultimately, some five generations. Like Noble Jones, Benjamin Sheftall (1692-1765) and his wife Perla were present at the creation of the earliest squares in 1733… but it was their great-great-great grandson Isaac Cohen Hertz (1849-1875) who would, as a toddler, see the creation of the last squares of Savannah’s City Common.

The first four…

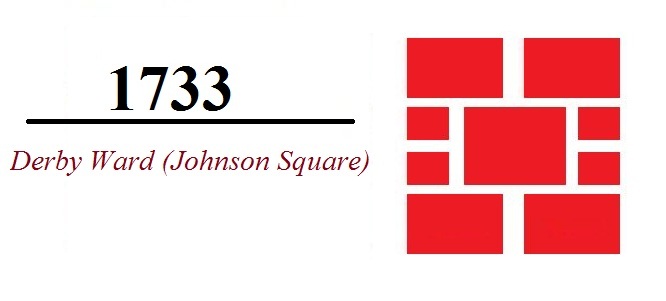

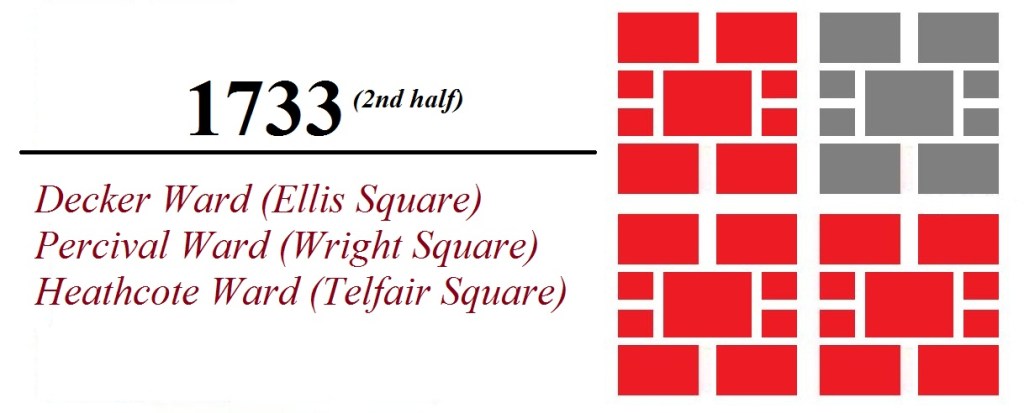

Johnson Square was officially marked off on the ninth day of the Savannah settlement; despite the best efforts of the colonists, this first ward—Derby Ward—was all that existed as late as August, 1733—though given the fact that Oglethorpe had named additional streets one month before in July it is clear other wards were in the process of being cleared. By December of 1733 four wards had some physical existence; Oglethorpe remarked in a correspondence to the Trustees of “three wards and a half taken up,” by the populace. Johnson Square appears to have been the only square to have had a name distinct of its ward until the 1760s. It should be noted at this point that in most cases the squares shared the same names as their respective wards, in many cases the names would differ. Different appellations in bold.

- Derby Ward = Johnson Square

- Decker Ward = Ellis Square

- Percival Ward = Wright Square

- Heathcote Ward = Telfair Square (originally St. James Square)

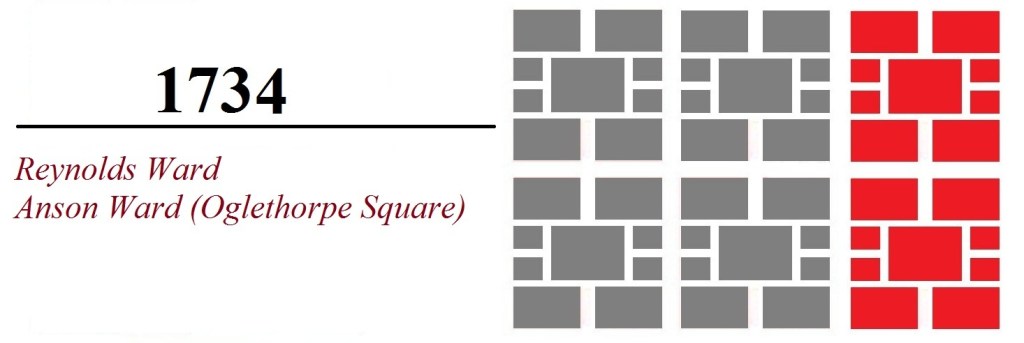

- Reynolds Ward = Reynolds Square

- Anson Ward = Oglethorpe Square

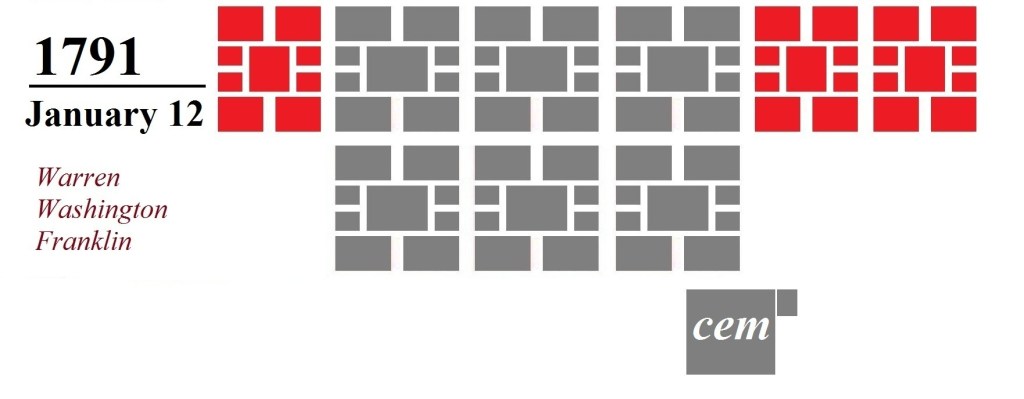

- Warren Ward = Warren Square

- Washington Ward = Washington Square

- Franklin Ward = Franklin Square

- Columbia Ward = Columbia Square

- Greene Ward = Greene Square

- Liberty Ward = Liberty Square

- Elbert Ward = Elbert Square

- Jackson Ward = Orleans Square

- Brown Ward = Chippewa Square

- Crawford Ward = Crawford Square

- Pulaski Ward = Pulaski Square

- Jasper Ward = Madison Square

- Lafayette Ward = Lafayette Square

- Troup Ward = Troup Square

- Calhoun Ward = Taylor Square (originally Calhoun Square)

- Wesley Ward = Whitefield Square

The six of Oglethorpe’s tenure…

House lot assignments in the fifth and sixth wards began in 1734, though it seems these wards five and six had been envisioned from the start. In early 1734 colonist Peter Gordon returned to the offices of the Georgia Board of Trustees, bearing an illustration that was soon to become the header of this blog, and to report of the settlement’s progress. President of the Trustees, John Percival, recorded the visit in his February 27, 1734 Journal entry.

“Mr. Gordon 1st Balif of Savannah lately come over to be cut for a fistula, attended, and presented a draft of Savannah wch. We ordered to be engraved. He gave us an acct. of the State of the Colony…. Mr. Gordons acct. of the Colony at the time he left it, November last, was…. That the town was intended to consist of 6 Wards, each Ward containing 4 Tythings, and each Tything 10 houses, So that the whole number of houses & Lots would be 240.”

– John Percival, Egmont Journal, p. 43-44

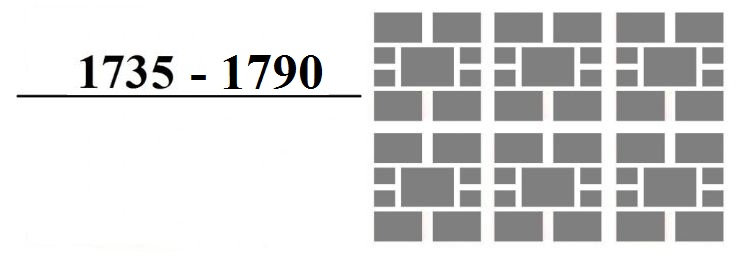

With the ability to accommodate 240 families, the colonial settlement of Savannah was viewed as complete. In short… there is no evidence to suggest that Oglethorpe designed, intended, or even imagined the need for more than six wards. With these six wards the town would remain largely static for the next six decades.

Colonial Era Savannah…

With Oglethorpe’s plan established, the next several decades saw very little advancement or further development. Oglethorpe had designed a Colonial town for 240 families; this done, the town’s geography settled into relative stagnation. With the exception of the cemetery—which began growing to the south of Anson Ward in the 1750s—little changed within the Common (… yes, ironically, the cemetery grew faster than the town during this era). But there was growth behind the scenes; though not represented within this City Common; the Yamacraw suburb was sold off into city lots in 1760. By 1771 William DeBrahm noted that both Yamacraw and Trustees’ Garden area were “increasing since 1760 extremely fast.”

Bulletpoints:

- This six-ward iteration of the town remained unchanged for nearly six decades

- As the town was at Oglethorpe’s departure so it remained when Oglethorpe died in England

- During the 1750s the (later South Broad Street/today’s Colonial Park) cemetery began use

- Also during the 1750s the policy of use of trust lots exclusively for public buildings was discontinued

- This was the tiny town of Savannah when Nathanael Greene lived and died at Mulberry Grove

- This was Savannah as it saw its incorporation into a city in 1789

- In July, 1737 John Wesley tallied a population of Savannah he estimated to be 518

- In 1760 Savannah had an estimated population of 970

- In 1780, during the depths of the Revolutionary War, Savannah had an estimated population of 750

With the Revolution over and the incorporation of the city, the 1790s saw growth replacing stagnation, and the wards began anew.

Imitation as the sincerest form of flattery…

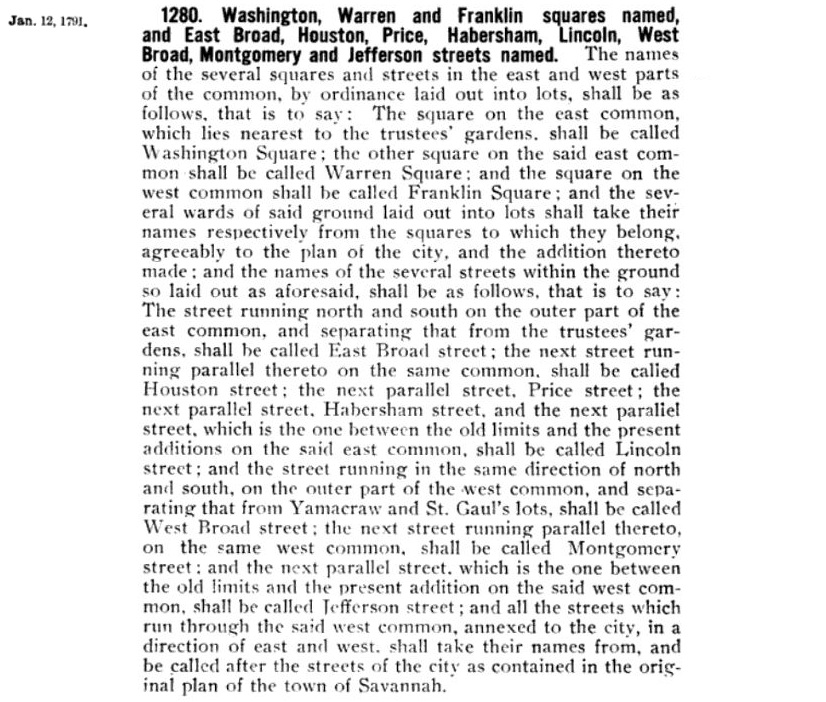

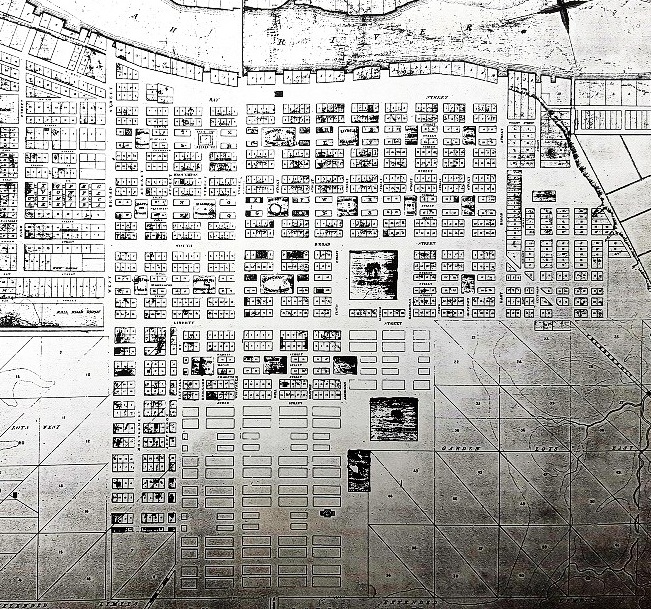

Finally, more wards! It is a testament to Oglethorpe’s plan that when in the 1790s population finally warranted further expansion of the city that the City Council made the fateful decision to continue his template of the wards. Two generations after Oglethorpe’s Colonial town had been “completed,” three additional wards were created, following the same character as his six. In many ways 1791 was a pivotal year; the first six decades had seen just six wards… but the next six decades would see the City Council adding 18 additional wards. The creation dates for all wards between 1791 and 1851 were recorded in the Minutes of City Council.

From the Proceedings of Council:

And with one fell swoop, the streets of Montgomery, Habersham, Price, East Broad and West Broad came into being in January of 1791.

The early Federal wards of 1791 differed slightly from Oglethorpe’s original six in that they lacked the width of the original wards. This was given to the fact that the parameters of the City Common, ill-defined in Oglethorpe’s time—and not at all defined when the first ward was surveyed on the ninth day of the settlement—were now well established, and Oglethorpe’s old ward template, measuring 675 ft by 675 ft, proved too large to fit without running into the old garden lots and private property. The consequence was that these wards flanking to the east and to the west were streamlined a bit, the length the same but the width more narrow. They and all that would follow them on a southerly line were to be compressed—eight tything lots instead of ten; the other four house lots per ward carved out of the trust lots so that, while narrower, each ward still contained 40 house lots.

- This was the nine-ward iteration of the town that would see Washington’s visit in May of 1791

- This explains why the square to the east and to the west are narrower than those toward the center of town

- This was the profile of the town when the fires of November and December of 1796 occurred

- The DeBrahm Map (c.1771) illustrated an Indian burial mound on ground that may be interpreted as bordering Warren and Washington Wards

- In 1794 Savannah had an estimated population of 2500

Following a rapid recovery in the wake of the 1796 fires, three more of these early Federal wards were laid out. The city now consisted of twelve wards; six from Oglethorpe’s Colonial era of the 1730s and six from the early Federal era of the 1790s. Over the next decade, as wealth trended toward the west end of town, Liberty Ward became a magnet for the more affluent, home to wharf owners John Williamson and William Taylor; on the eastern end of town Greene and Columbia were decidedly more middle/lower class.

- It is ironic that, in tour-guide lore, these 1790s wards are often referred to as the Colonial District when they are, in fact, demonstrably Federal

- By 1799 most of the squares had cisterns and public water pumps as their center

Welcome to the 19th century…

With the turn of the 19th century, the city first breached the confines of South Broad Street (our current Oglethorpe Avenue). Today Oglethorpe remains something of a visible seam of the downtown patchwork; while driving to and fro on the old boulevard it is fun to recognize that everything to the north of Oglethorpe was 18th century layout, but everything to the south, 19th century addition.

- On the north-west end of the Common, today’s Williamson Street corridor north of Bay Street was carved out in July of 1803, as the city surrendered that portion of the Strand

- 1803 also saw the renaming of King, Prince and Duke Streets to the more recognizable names of today

In the 20th century all three of the Montgomery Street squares would be subject to upheaval as the street was allowed to be run through them. Franklin Square was restored in 1984; Liberty and Elbert remain today only partial slivers.

“Savannah as a town is increasing, but it has no charms. It is a wooden town on a sand-heap. In walking their streets you labor as much as if you was wading through a snow-bank, with this difference only–you must walk blindfolded, or your eyes will be put out. It resembles my idea of the Arabian deserts in a hurricane. No lady walks the roads, and the inhabitants never with pleasure, excepting after a rain; the least breeze of wind moves in clouds the sand through every street.”

– Jonathan Mason, March, 1804 (source)- This was the Savannah that would soon see two new cemeteries laid out on the South Common (but more on these later)

- In 1804 Savannah had an estimated population of 5046, another indication of a city on the rise

Post War of 1812…

Savannah’s population doubled in the ten-year span between 1794 and 1804. Now the town was spreading quickly, with the creation of nine wards in 24 years. These ward and street names of 1815 represent the only lasting impact of the War of 1812, which never touched Savannah but had terminated only months before. These were the first wards in 81 years to observe the 675 x 675 footprint of the wards adjoining them to the north. As a July 23, 1816 City Surveyor’s report noted: “The new Wards… have been laid off to Correspond with those of the old town,” meaning Oglethorpe’s first six.

- This was the town of Savannah that would witness the visits of President Monroe in 1819 and Lafayette in 1825

- This was the town that would be ravaged by the Fire of 1820 and the subsequent Yellow Fever epidemic

- This was the town that would see the economic highs of the 1810s and suffer the depression of the 1820s

- This was the town that would see the erection of its first public monument (the only monument to exist during the “squares creation” era)

- This was the town that would see the earliest beginnings of canal building and the incorporation of the railroad

- In 1815 the very earliest River Street properties standing today were still new or in the midst of construction

- All William Jay properties were erected during this era

- In 1819 the poor house and hospital was created on the wilderness at the border of the South Common

- In 1810 Savannah had a population of 5215

- In 1820 Savannah had a population of 7523

- In 1830 Savannah had a population of 7773

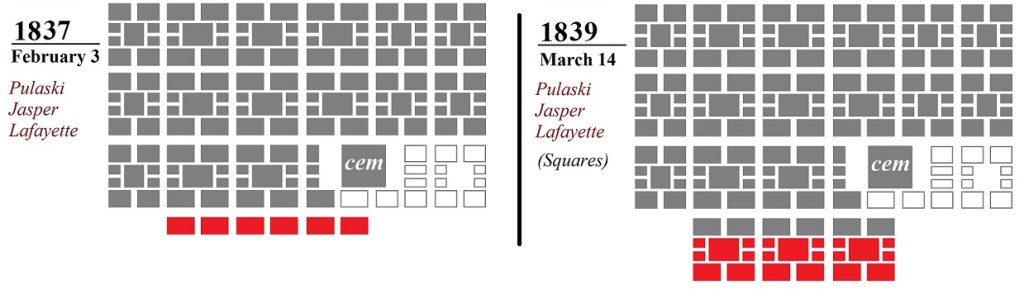

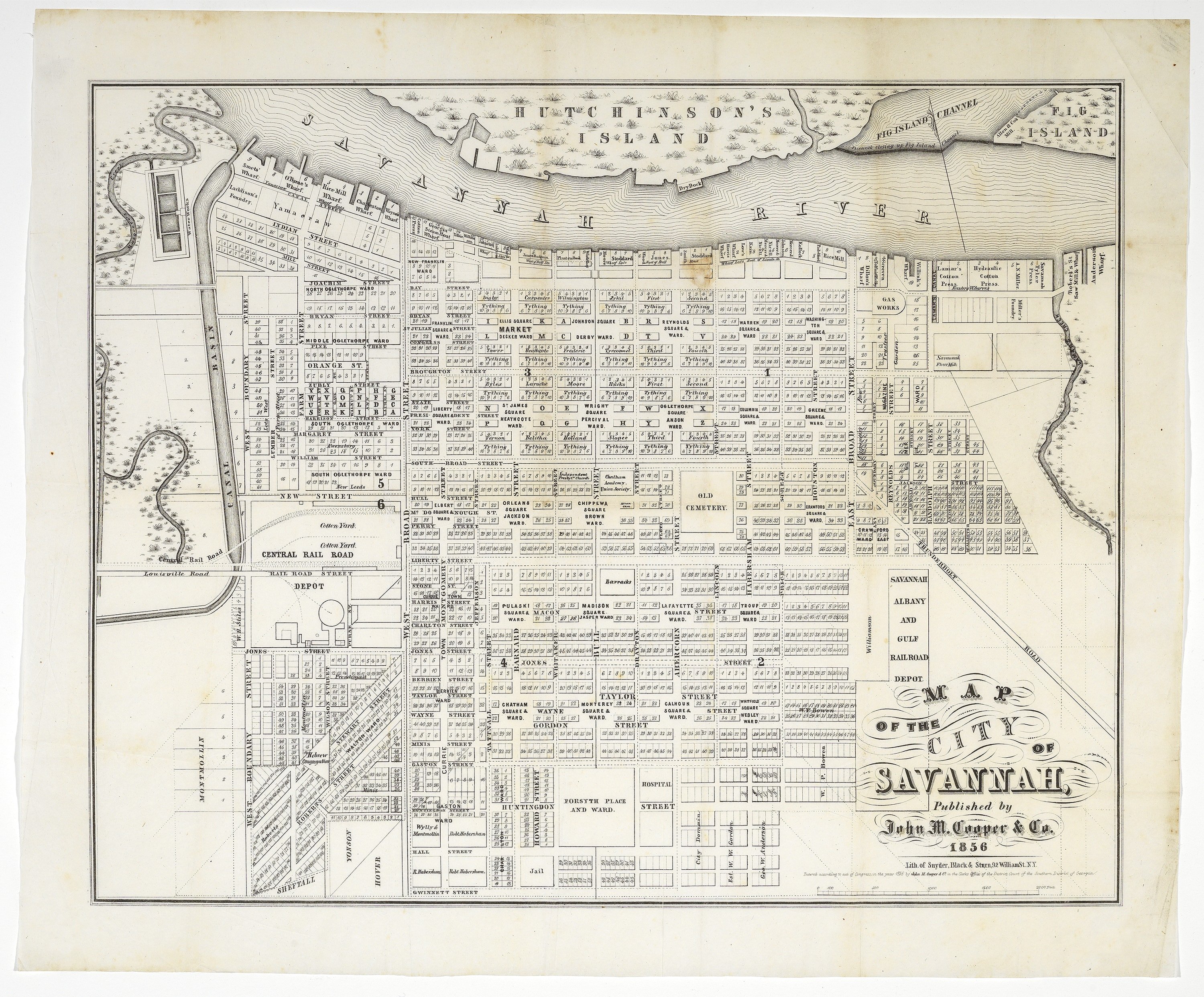

The only wards laid out incrementally…

Another official barrier broken in 1837 as Liberty Street was created and breached, but interestingly… only by tything lots. These three wards south of Liberty were laid out in a two-step process; in 1837 City Council laid out the northern tything lots and established the wards’ existence to Harris Street as the southern boundary. This was due to fact that the northernmost tything lots of today’s Jasper Ward effectively already existed. Following the dilapidation of the former Barracks south of the old Fort Wayne in Carpenters Row during the 1810s, Federal funding had been discontinued, but by the mid 1820s negotiations with the Federal government had resulted in a new “Oglethorpe Barracks” south of Liberty (on the site of the Desoto Hotel today), first appearing in print in 1827. In 1839, two years after the 1837 northern tything layout the City Council officially completed these three wards by designating their squares, trust lots and southern tythings and streets.

By this point (if not earlier) the undeveloped Common to the south was cleared land, as Charles Olmstead recalled looking out from Harris to the south and finding it essentially a meadow.

“On the south, Harris street was the limit in 1840 excepting in the eastern and western suburbs. I distinctly remember standing in 1846 or 7, at the corner of Oglethorpe Barracks, where the Desoto Hotel now stands, and seeing no buildings south of me but two which had recently been erected, the residence of Mr. John N. Lewis on the S.W. corner of Bull and Charlton streets, and that of the Gallaudet [family] on Jones street…. Toward the south-east was the old county jail and its enclosed yard occupying ground on which the handsome Low and Cohen residences were afterwards built. From Harris street to Gaston the city common extended, a broad grassy stretch of land much frequented in the summer season by sportsmen for shooting night-hawks. At Gaston street the pine forest began and continued indefinitely to the south except where broken by a negro cemetery, and the stranger’s burial ground….”

- This was the Savannah that was now actively engineering in canal-building and beginning construction of the railroad on its west side, diving into debt with the Central of Georgia

- This was the town that saw the US Barracks move from the old Ft Wayne site to Liberty Street

- This was the town of Cerveau’s iconic Savannah 1837 painting (below)

- This was the town that would see the earliest adoption of oak trees in the downtown space

- In 1840 Savannah had a population of 11,214

The presence of the cemetery had complicated the layout for decades as the wards were forced to spread around the old burial tract. To be clear, Crawford Ward was illustrated intact on maps as early as 1820, but this “ward and a half” by the name of Crawford was officially carved out and recognized by City Council in 1841, two years after the squares of Pulaski, Madison and Lafayette. Though the square itself was small… due to the geography of the old cemetery the ward was laid out to include some 80 lots, twice the number of a typical ward.

- This was the Savannah that would see two brand new cemeteries quietly added to the east of the hospital by 1846

- This town of early 1840s was the Savannah of Charles Cluskey, witnessing the erection of the Cluskey Vaults—the first permanent River Street embankment construction—and Cluskey’s Marshall commercial properties on Oglethorpe Square and the Sisters of Mercy/St. Vincent’s Academy complex

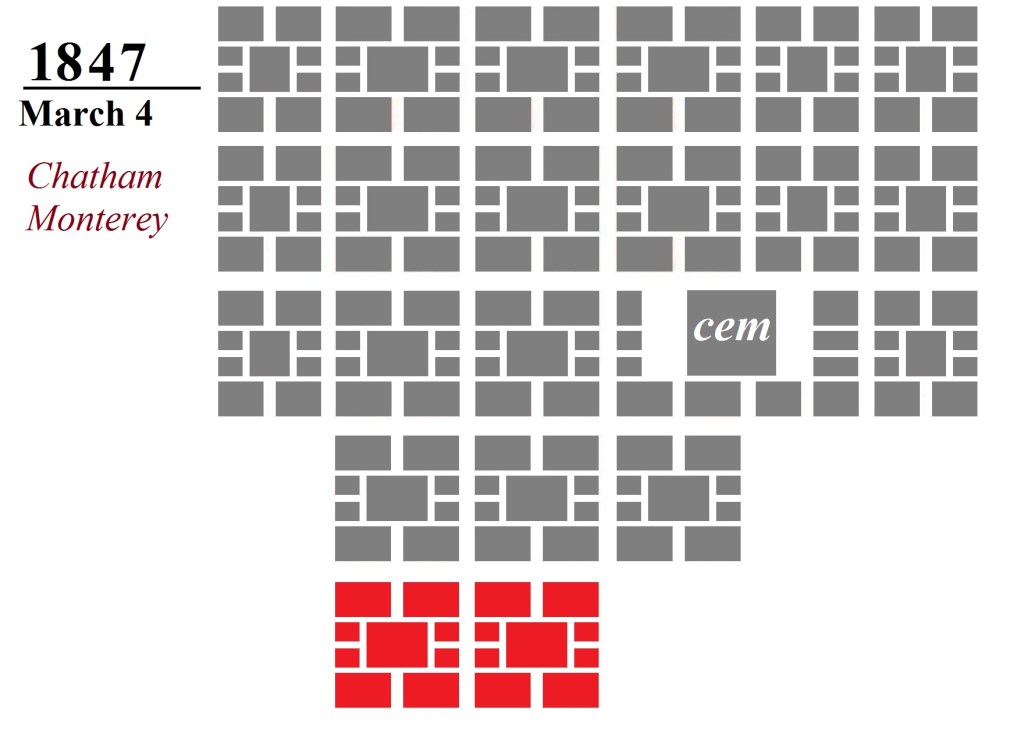

The “high Antebellum” squares…

Chatham and Monterey wards may be seen as the embodiment of the full flourish of Antebellum prosperity. Like the wards that followed the War of 1812, Monterey Ward owed its name to recent current events—the Mexican War’s Battle of Monterey had occurred only eight months before. Chatham Ward, in the meantime, looked back to William Pitt, the Earl of Chatham, one of the American Colonies’ staunchest supporters who had suffered a fatal stroke in Parliament in 1778 following an impassioned plea for reconciliation with the Colonies, and began the mid-19th century tradition of eschewing recent history for much earlier antecedents (Gaston, Huntingdon, Hall, Gwinnett & Bolton streets, etc).

- In 1848 Savannah had a population of 13,573

- In 1850 Savannah had a population of 15,312

- According to the 1848 Bancroft Census, the three most populated wards were Derby (706), Heathcote (681) and Washington (645)

- In 1848 Washington Ward was still without a single brick structure

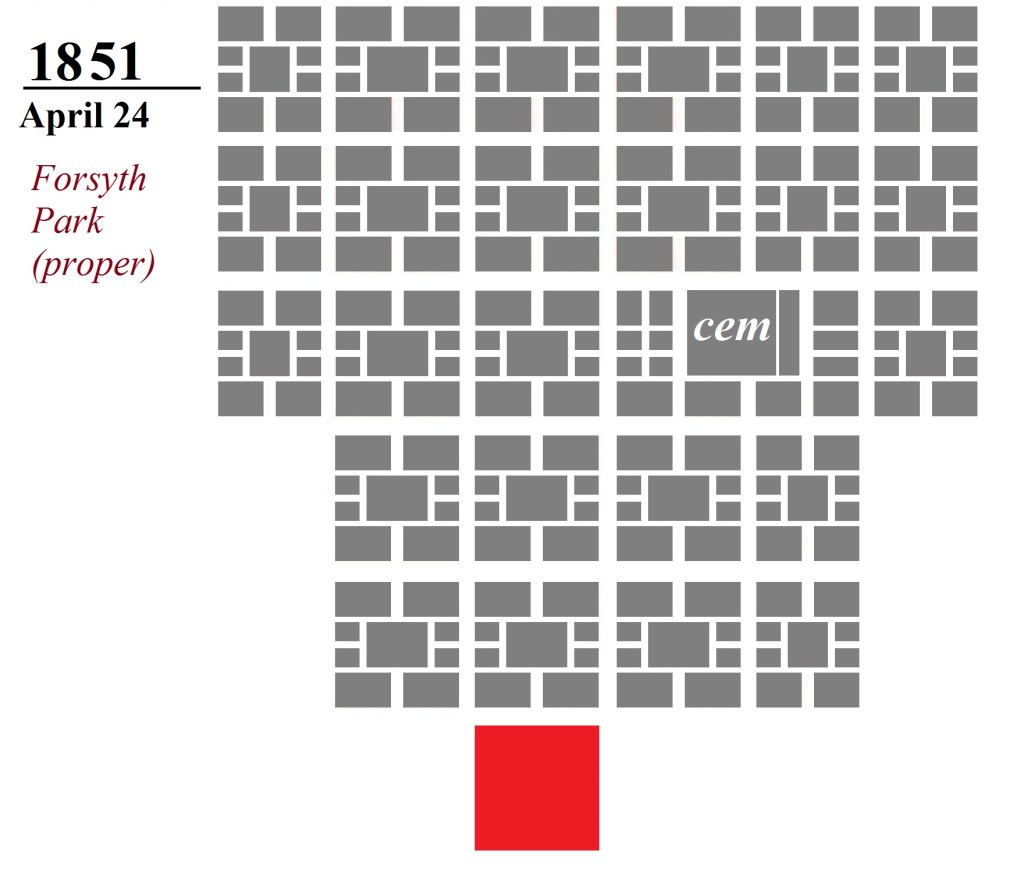

The last three…

In 2023, Calhoun Square was renamed Taylor Square, honoring Susie King Taylor (1848- 1912). Born a slave and educated within a secret school in Warren Ward, the young Taylor became a nurse during the Civil War and was the first woman of color to publish a Memoir, “Reminiscences of My Life in Camp With the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers.” John C. Calhoun? Yes, he’s the guy with a large obelisk in Charleston (…but we all know what they say about large obelisks). Seriously, in the ’80s I lived on Jones Street and Calhoun Square happened to be my nearest square. It formerly hosted the annual schoolchildren’s May Day maypole celebrations, hosted in part by Massie School, excavations around which have frequently turned up bodies… which I should probably address right about here.

So one of the disturbing aspects about Calhoun & Wesley Wards (or Taylor & Whitefiled Squares) is that both were developed—in part or whole—over cemeteries that had been created by the prior generation… a generation which, in fairness, did not imagine their children or grandchildren would actually intend to later build upon. (We’ve all been there; it’s only later you realize, oh, I shouldn’t have put a cemetery there.) In the autumn of 1810 the City Council set aside a parcel of land on the South Common “as the burial place for people of colour.” According to an 1813 ordinance, this cemetery measured 300 feet by 650 feet, and its western boundary was just to the west of today’s Lincoln Street. Nine years later, on July 26, 1819 a committee was formed to consider “the laying off a piece of ground for the interment of strangers.” This “new cemetery,” adjoining it to the west and coinciding with today’s Calhoun Ward, was intended for the interment of residents without families already in the South Broad Cemetery.

“Even as late as 1851 I used to go through these burial grounds with my bow and arrow shooting sparrows and other small birds. I do not recall if I ever saw a tombstone in either of these cemeteries, but the grave mounds were numerous, those of the negroes being plainly indicated by the ornaments laid upon them.”

– William Harden, Recollections of a Long and Satisfactory Life, p. 57

Unlike the 18th century—where the expanding physical parameters of the graveyard outpaced the stagnation of the town—by 1851 the city was looming over the lands of the dead. In 1855 the Mayor’s Annual Report recorded expenditures between November of 1854 and November of 1855 amounting to $722.75 for the removal of the bodies from the Negro Cemetery to Laurel Grove. “The rapid extension of the city southward, the dilapidated condition of the old negro cemetery, and the rude assaults of sacrilegious hands upon the repose of the dead, rendered it necessary to remove the remains of colored persons to the appointed for their sepulture near Laurel Grove Cemetery.”

While many of the interments from the Negro Cemetery were removed, the fact that many of Savannah’s more prominent 19th century African-American figures remain missing in death (looking at you, Catherine Deveaux) and the fact that remains have been disturbed during countless 20th and 21st century excavations in and around Calhoun/Taylor Square, would indicate that neither cemetery was relocated in full.

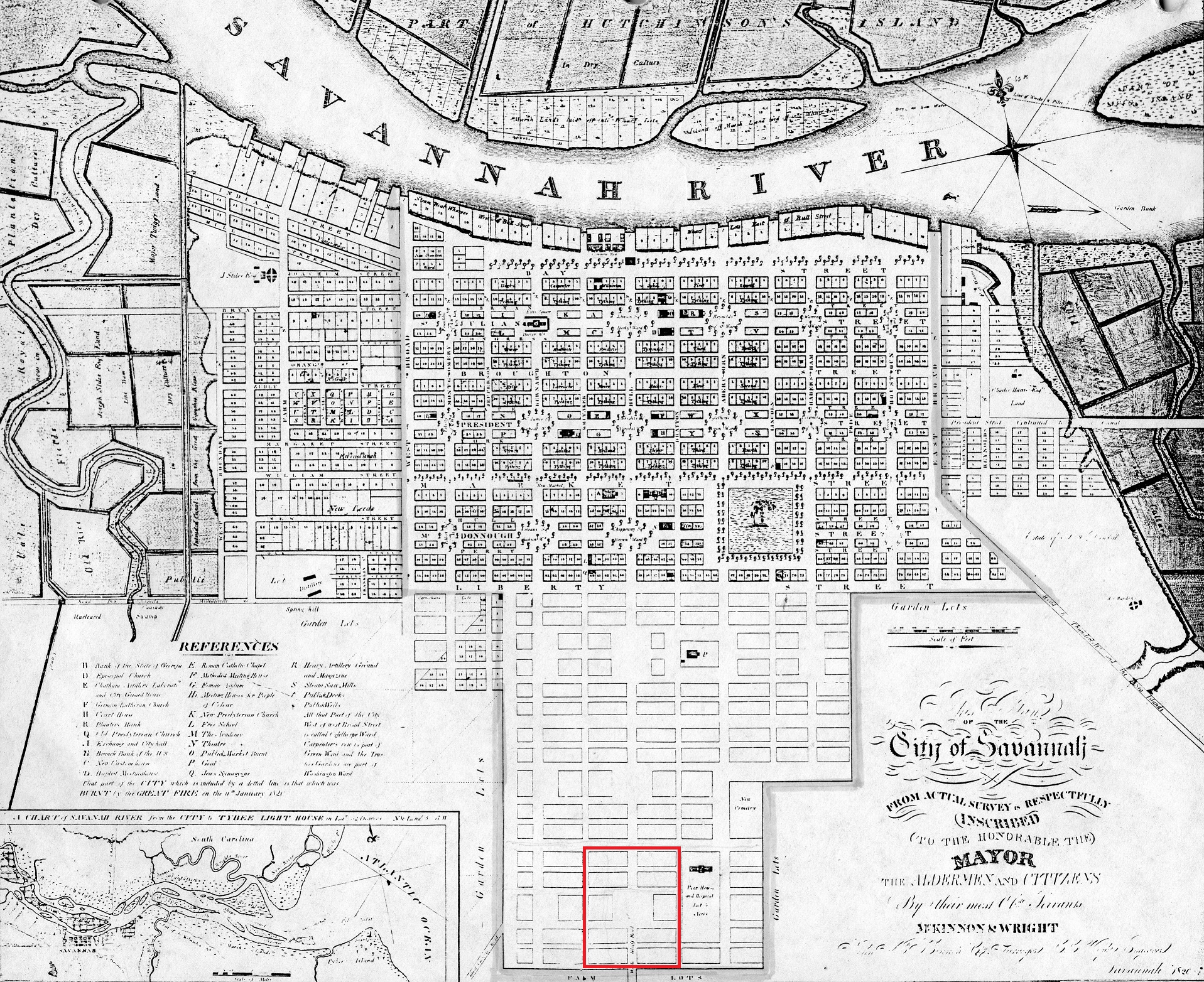

Compellingly, given the tapering design of the City Common, there was an option to place a twenty-fifth square (feels like a #hashtag, but I won’t…) to the south. As far back as 1820, the McKinnon Map had actually presumed that there would be a square on the site.

Some 31 years after this conceptual imagination—and just one month after the last three wards were laid out—the City Council decidedly went an unexpected route, opting for an entire ward-sized park.

By this point the squares were fenced-in public spaces and grazing ground, but not generally treated as actual parks. Even by this point in 1851, only one monument existed in a Savannah square, that being the Greene & Pulaski Monument in Johnson Square; two years later the Pulaski Monument would be erected in Monterey. Forsyth Park (later unsuccessfully petitioned to be renamed Hodgson Park) was envisioned and designed in 1851 as a Victorian-era urban forest, a retreat of nature consuming the length and breadth of an entire ward. Its southern boundary was originally today’s Hall Street; in 1852 “Forsyth Place” was fenced in. On February 6, 1867 the City annexed the nearby military parade grounds to the south, dramatically enlarging the park with its new “Park Extension.”

It is easy to see a unique genius in all of Savannah’s squares now, but what we see today was a creation across multiple generations—continuing, altering and in some cases improving the interpretation of Oglethorpe’s concept. Today’s result is an imperfect organism; the cemetery and its surroundings obstructed the layout, streets have appeared and disappeared and entire squares have come and gone (and come again… Franklin and Ellis, while only Liberty and Elbert remain Montgomery Street slivers). From one ward to 24 in under 120 years, the City Common today is a patchwork of decades of different people interpreting and reinterpreting an elegant idea that was never explained by one Mr. Oglethorpe.

In the next post we’ll examine how the squares evolved into parks…