All research and commentary by Jefferson Hall

The unlikely story of a slave mart in the middle of town, exchanging whips and chains for pencils and paper… and hope

For years, history has celebrated the accomplishments of the West Broad Street School and the Beach Institute as early centers of African-American education in the years following the Civil War. Considered objectively, however, these schools were relatively late-comers to the scene. The West Broad Street School opened in 1878, and by the time the Beach Institute opened in 1867 it was replacing no fewer than half a dozen schools already existing within Savannah’s African-American community. In March of 1866, the Savannah superintendent of Freedmen’s Schools made reference to a total of six schools:

So while the Beach Institute today garners much-deserved attention, this overlooks the fact that there was an entire contingent of schools that existed on the streets of Savannah in the era between 1865 and 1867. Lost in the shuffle, forgotten, confused or ignored is the epicenter, the ground zero; the first school opened by the Savannah Educational Association in the waning days of the Civil War… the Bryan Free School. Housed within a federally-seized slave mart property, the school was opened in early 1865, predating the Beach Institute by a full two years. Today this building at 21 Barnard Street is just another building within City Market. But the legacy it carries is rich… and virtually unrecognized.

The Reverend James D. Lynch (1839-1872) was a northern Black missionary who came to Savannah in the days following the entry of Sherman’s army into the city. On January 4, 1865, shortly after his arrival, he wrote a letter to The National Freedman, discussing wide-ranging issues from the fact that there had not yet been an emancipation announcement (which would be rectified in part twelve days later with Field Order #15) to imploring funds for the great task ahead of establishing an educational community.

“My Dear Sir,

I have been here for some days. The colored people did not seem to realize that they were free, as their status was not announced by any proclamation….

There are a great many very intelligent colored persons in Savannah. We have been holding large meetings of the colored citizens. The interest evoked has been great, and the promise of good being done is bright.

We have secured from the Government the use of three large buildings.

1. ‘A. Bryant’s Negro Mart’ (thus reads the sign over the door). It is a large three-story brick building. In this place slaves had been bought and sold for many years. We have found many ‘gems’ such as handcuffs, whips and staples for tying, etc. Bills of sales of slaves by the hundreds all giving a faithful description of the hellish business. This we are going to use for school purposes.

2. The Stiles house on Farm Street, formerly used as a rebel hospital, we have also secured for school purposes.

3. A large three-story brick building on the lot adjoining for a hospital for freedmen.

We have organized an Association called the Savannah Educational Association, composed of the pastors and members of the colored churches. There are five very large colored churches in this city, four of them will seat one thousand persons each. Three have fine organs. That the colored people built such churches is astonishing. Hundreds of the colored people are joining the Association as honorary members.”

– James Lynch to The National Freedman, January 4, 1865

The above marked the beginning of the Savannah Educational Association, Black Savannah’s homegrown attempt to educate Black Savannah. As indicated above, the SEA made use of the Stiles house, formerly at Farm (now Fahm) and Joachim (now West Bay), as the Oglethorpe Free School, the second school organized by the SEA. This building is lost to us today, long gone beneath the pavement of West Bay Street. Similarly, the Hospital School is gone as well; any trace of the structure likely removed when the hospital was rebuilt in 1877.

But the Savannah Educational Association’s first school building still stands today.

“The Bryan School House – This large and commodious building, corner of St. Julian and Barnard streets, west of the market, at the present time used as a school house for the colored citizens of Savannah, has a very interesting history connected within its walls. It was built about fifteen years since by John S. Montmollin, a trader in slaves. His death occurred about seven years ago by the explosion of the boiler of the steamer John G. Lawton, his head and upper extremities lodging in the mud; in this condition he was found, and brought to this city and buried. His property then fell into the possession of Alexander Bryan, who until a few days prior to the occupation of Savannah by the Federals used the premises as a jail and office for the barter and sale of slaves.”

– Savannah Daily Herald, March 20, 1865

In today’s City Market concourse two buildings adjoin one another… both of which had been built as slave brokerages. On the northern side, facing Bryan and Barnard at 19 Barnard Street, is a structure built for David R. Dillon in 1855. Its southern neighbor, facing St. Julian and Barnard at 21 Barnard, seems to have been completed the following year, in 1856, for John S. Montmollin. The Tax Digest (GHS coll. #5600CT-70) of 1856 valued the tax assessment of Montmollin’s lot at $4500, but by 1857, his “1/8 Lot I & Impro., Decker Ward” was valued at $11,500. Since tax digests reflect the value of the year preceding, this suggests that the building was erected between 1855 and 1856. (Note: “Impro.” means whatever recent “improvements” have been made to the property in question.)

Both properties are found within the “Morrison Book.”

Montmollin and the back story of 21 Barnard

In June of 1852 two giants merged. George Wylly and John Montmollin entered into a partnership which lasted for the next four years, as Wylly & Montmollin came to dominate Savannah’s commercial landscape. As “commission brokers,” they did not engage exclusively in the slave trade; commission brokers trafficked in real estate, stocks and commodities—in short, the buying and selling of any kind of properties. In perusing the newspaper ads of the 1850s, some commission brokers evidently chose not to engage in the selling of slaves… others were not so discerning. Slave trading in the 1850s could represent a lucrative portion of any commission broker’s business. The leased office of Wylly & Montmollin was listed at the “corner of Bay Lane and Bull st, rear of the post office;” this would suggest offices at the back of the Custom House, facing the lane. Their advertisements in the Morning News are found as a daily column, where available real estate and slaves were interchangeably listed without discrimination.

Following the dissolution of Wylly & Montmollin on March 1, 1856 Montmollin moved to an office on “Bull St. opposite Pulaski House” and opened a brand new enormous storehouse on Decker Ward’s Trust Lot “I,” (today’s 21 Barnard Street, pictured above) where he advertised corn, wheat and slaves “at Montmollin’s Building, west side of Market Square.” The Tax Digests reveal Montmollin grossed nearly $70,000 in commissions in 1856 alone. Montmollin’s enterprise was huge, and he certainly did not shy away from slave sales, which constituted a considerable portion of his business.

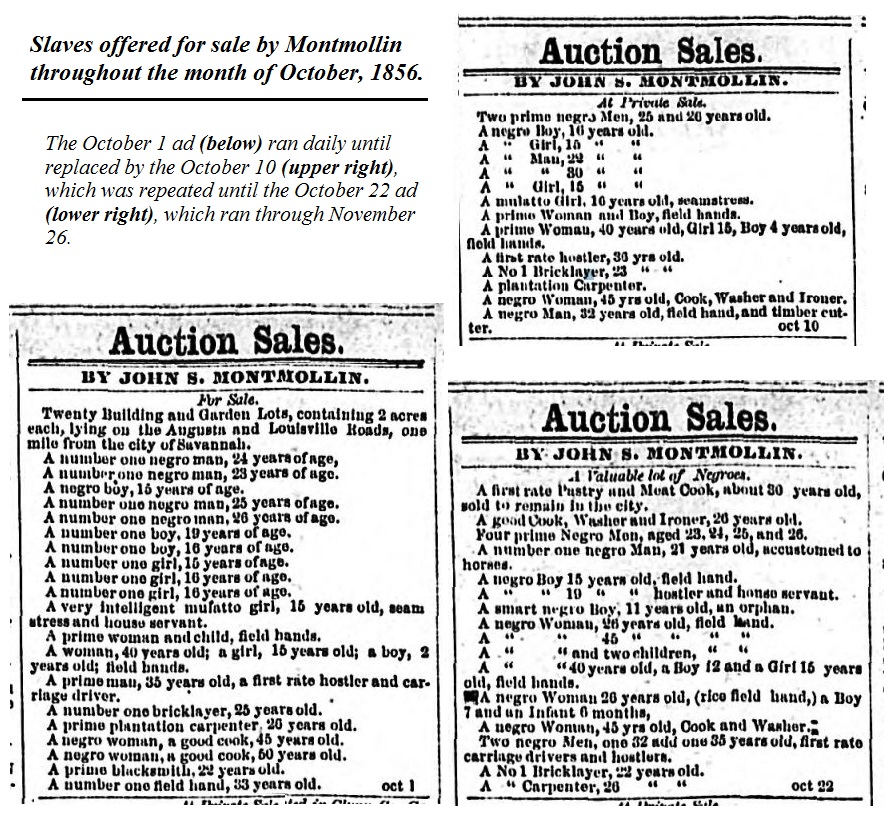

These advertisements appeared daily in the Savannah Daily Republican, the October 1 (listing 23 individuals) ad giving way to the October 10 (with 18), which was replaced by the October 22 (26 persons). Sixty-seven people were advertised for sale inside a span of four weeks.

“The building is in condition and order for the safe keeping of negroes,” Alexander Bryan would later advertise of this Montmollin property. This and the fact that the building was sometimes referred to as a “jail,” indicates that it was used as a public lockup for slaves. The basement level served as a short-term below-grade holding pen, more commonly referred to as a “jail.” In addition, the building appears to have had a private auction room or rooms—“Rooms large and pleasant,” Bryan boasted. Montmollin was the agent of sale; individuals that were listed on the market could have been kept on premises within the facility, they might have resided with their former owners until a sale was concluded, they could have been kept at Montmollin’s South Carolina plantation fourteen miles up the Savannah river, or they could have been interned at William Wright’s large slave yard and public lockup, which was just two blocks away on Bryan Street. These commercial slave yards were public venues accommodating short-term (or even long-term) holding. Though the analogy is crude, these lockups were not unlike the public stables around town, where for a fee one could keep one’s property… in this case, a person or persons.

Montmollin blows up, Bryan enters

Long a proponent of the reopening of the Atlantic slave trade; in 1858 John Montmollin took an active role toward achieving this goal. As a financial backer of the racing yacht-turned-slave-ship known as the Wanderer, Montmollin was a partner in the illegal trafficking of African men and women to Georgia soil in December, 1858. He may have even kept a contingent of these trafficked individuals at his plantation, though a federal jury ultimately declined to indict him. Six months later, in June of 1859, the 51 year-old Montmollin came to a grizzly end, killed in a boiler explosion on the river, as the Daily Herald later remarked without sentiment, “his head and upper extremities lodging in the mud.”

Following Montmollin’s death, his business was taken over—and the building leased—by Alexander Bryan, who placed a sign over the doorway reading “A. Bryan’s Negro Mart”. The property was advertised frequently in the Savannah Morning News and listed as Alexander Bryan’s place of business in the 1860 City Directory.

For eight years, and under two proprietors, this property at 21 Barnard endured as an office of slave sale. Then, in 1864, with the arrival of Sherman’s army, the Federal government seized the building and gave it to Savannah’s African-American community. They, in turn, created from it in early 1865 Savannah’s very first legal and legitimate Black school, the Bryan Free School. From slave house to school house, this building stands as a testament to the very best—and the very worst—of the African-American experience in Savannah.

“For the advancement and elevation of colored children”

The Bryan Free School had as many as 450 students. James Porter became the principal of the school; while he later went on to helm the West Broad Street School and would soon be elected to the Georgia State Legislature, in early 1865 the Bryan Free School represented a high point for him, for the SEA and for Savannah’s African-American community. Porter had come to Savannah in 1856 and risen quickly to become one of the Savannah’s most prominent figures within the freedmen community. As Charles Hoskins noted:

“Porter soon established yet another school for blacks and used his trade as a tailor to cover up his school activities. Frank Bynes reported that Porter’s tailor shop was located at 177 [Bryan] Street. According to Professor Morse, Porter’s school ‘had a trap door where, when about to be surprised or apprehended, his pupils might save themselves.’”

– Charles Lwanga Hoskins, Yet With a Steady Beat, 2001, p.164

It is interesting to note the address that Frank Bynes suggested, if correct, is today’s 219 West Bryan, in the 1855 building that adjoins the slave brokerage of David Dillon and is only feet away from the Montmollin/Bryan property. Intent on “second-sourcing” this claim I perused the City Directories between 1858-1860, but as African-Americans were not typically listed in the time period, I was unable to find confirmation of Porter’s tailor shop location… but I found nothing to dispute the claim either. Ironically, Porter’s Antebellum school could have been operating one wall away from two slave brokerages.

On July 7, 1865, the Savannah Republican recorded a public “open house” offered by the school, attended by the newspaper and dignitaries. The Republican marveled over the property’s transition from a “hall which not many months since resounded with the cries of the slave dealer as the auctioneer cried down men, women and children, to the highest bidder.”

In addition to housing a school, the building also acted as a community center, regularly hosting large meetings and concerts.

In April 2024 the City of Savannah and the Georgia Historical Society unveiled a marker at the corner of Barnard and St. Julian, recognizing the history of the building.

The old Montmollin warehouse at 21 Barnard today shows little obvious evidence of its complicated story, but in 1865 this was one of the most important buildings in Savannah. It marked an end; it marked a beginning. It was a transition, and all that came after owed something to what began there. Once a slave brokerage, by 1865 it had been turned from a site of enslavement into a place of enlightenment.

“The building, it is certain, will never again be used for a slave trader’s office, but it should be kept for the purpose of educating the black race, and not to sell them.”

– Savannah Daily Herald, March 20, 1865

Related posts:

Savannah’s Clandestine Schools of the Antebellum Era

Savannah’s Slave Brokerages of the 1850s

3 thoughts on “From Slave House to School House: Rediscovering the Bryan Free School”