All research and commentary by Jefferson Hall

In the decades that lead up to the Civil War, where were enslaved persons sold? Where were they held… and do any of these sites still exist?

Savannah in the 1850s was a bustling center of commerce, and in many ways the embodiment of the Antebellum South. The prosperity owed its existence to an underclass visible on every street of Savannah, as anyone with a darker shade of skin was greeted differently or expected to walk on one particular side of the street, and some were simply sold away while others watched. Welcome to the world of the commission brokers, a class of businessmen who dealt in slavery as easily as real estate and bonds.

In a previous post we examined the origins of the slave trade in Savannah. But as we all know, the story of the purchase and sale of enslaved persons in Savannah did not end with the closing of the Atlantic trade; it simply changed form, altering and morphing to keep up with changing economics. To be sure, the numbers of enslaved persons to be brought to the auction block was smaller two generations later… but the individual lives impacted were no less important.

By 1790 the Chatham County court house on Wright Square had become a regular locale for slave auctions. Hosting monthly sheriff’s sales, it gradually became recognized as a place for all estate-related sales. After the turn of the 19th century, with the days of the Atlantic trade over, auctions became smaller and less frequent. As other sites ceased being used or were torn down, the platforms around the court house remained. Forget what you might think of any other potential site; for 75 years (1790-1865)—by far, longer than any other slave sale venue in Savannah—the Chatham County court house endured as a site of sale for enslaved persons. Through two iterations—the circa-1773 building and the 1833 building, a neo-Classical structure (pictured) which preceded the current 1889 W. G. Preston building standing today—the court house at the corner of Bull and President streets hosted three generations of human sale.

From the Savannah Daily Republican, March 4, 1856:

“When I was nine years of age Father took me down town to see the slave trading post, where he purchased a house girl for Mother, she having had considerable trouble with the white girls who went out to work. There was a high platform, which partly surrounded the Chatham County Court House, upon which the slaves were placed for sale. We looked them all over until presently we saw one who looked as if she would be just the one we wanted.

“‘Hey… what’s your name?’ asked Father.

“‘Elsie, Sur,’ answered she.

“‘What’s that scar on your leg and that scratch on your face?’ continued Father as he gave her the once over.

“‘That ‘er scar on my face is where My Missus done hit me with the strup, and I run away from her, this here hole on my leg is where a snake bite me and I took a knife and cut the bite out – and boss if you buy me an’ be good to me, I promise to work ‘til I die,’ screamed old Elsie.

“And so Elsie was our choice and Father paid $2500 for her in Confederate money. As we took her down off of the platform a storm of voices filled the air saying: ‘Buy Me, buy Me, boss, please do,’ while thin black arms waved to us as we drove off with old Elsie on the back seat of our carriage.”

– William H. Ray, undated

Recorded for posterity is the end to the County court house slave stands in 1865. Reduced in an instant to kindling, it was an event noted by the not-unbiased presses of the Savannah newspaper, which was now printed under the direction of Sherman’s army.

“In front of the Court House in this city there has been for many years a number of tables which were used by negro brokers as auction blocks for the display and sale of slaves. The stands have disappeared with the advance of civilization–Sherman’s Army–and have been used to warm Abolition bodies.”

– Savannah Republican, January 6, 1865

It should be understood that the men who engaged in the sale of slaves in this late period of 1840-1864 were not exclusively slave traders. Nor were they quite the “import merchants” we encountered in the 18th century… who rather cluelessly fell into the business of selling slaves. These men were “commission brokers,” agents who specialized in the buying and selling of any kind of property, whether it be real estate, stock notes, bank notes, commodities… or people. Commission brokers sponsored open auctions at the court house platforms and advertised private sales within the newspapers. To be clear, not all commission brokers engaged in the sale of enslaved persons; in viewing the records and advertisements today it is evident that many brokers chose to steer clear of this aspect of the profession; others however, were not so discerning. Some Savannah brokers of the 1850s who did demonstrably—and repeatedly—engage in trafficking included John S. Montmollin, George W. Wylly, William Wright, T. J. Walsh, Joseph Bryan, J. A. Stevenson, David R. Dillon and Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar… many of whom had offices on the same block.

Within the Georgia Historical Society’s library at Hodgson Hall, the printed volumes of Savannah’s City Directories begin in 1858, and within them one does not find any business listings therein for “slave sales,” or anything so straightforward. Instead, one must follow the trail of these commission brokers.

GEO. W. WYLLY

AUCTION & COMMISSION BROKER

Office corner of Drayton Street and Bay Lane

Savannah, Geo.

ATTEND TO THE PURCHASE AND SALE OF

REAL ESTATE, BANK STOCK, NEGROES, &c.

HAS CONTANTLY ON HAND

CARPENTERS, BLACKSMITHS, COOKS, SEAMSTRESSES,

AND FIELD HANDS

Liberal advances made on Properties consigned to him for sale

-Opening leaf of the 1860 Savannah City Directory

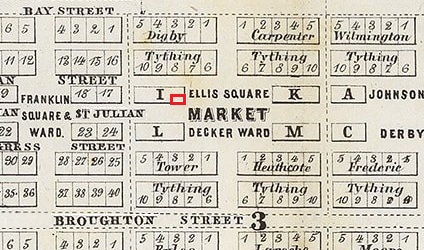

The advertisement above alludes to George Wylly’s location at the corner of corner of Drayton and Bull Lane (“e” on the Derby Ward graphic above). George Wylly and John Montmollin began a partnership in June, 1852.

Their leased office was listed at the “corner of Bay Lane and Bull st, rear of the post office.” (“a” on the above graphic) This description would suggest offices at the back of the Custom House, facing the lane, literally just feet from the slave yard and public holding pen that William Wright began in 1853 (“c”).

The advertisements of Wylly and Montmollin in the Morning News grow from infrequent in 1852 to a daily column by early 1856. Advertisements from 1855:

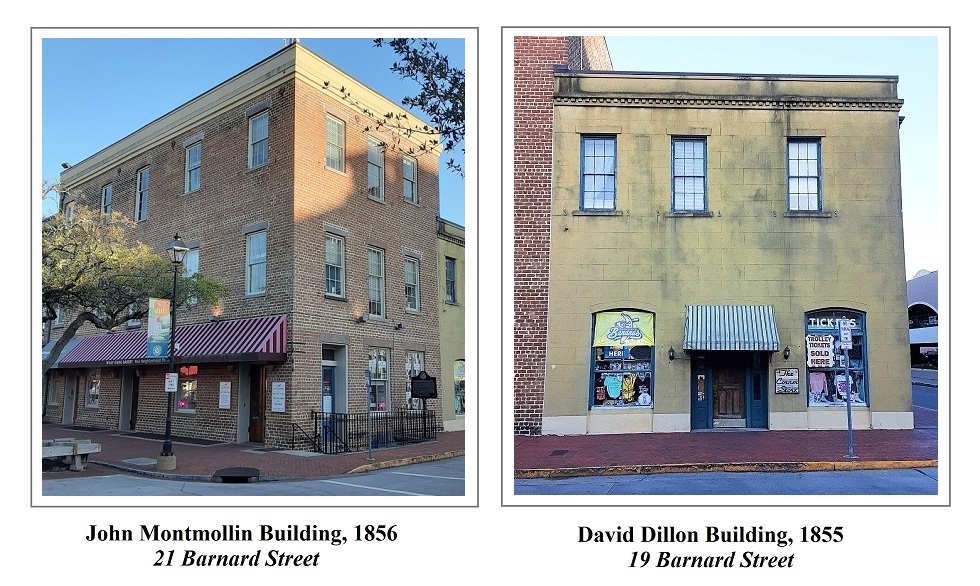

The partnership between Wylly and Montmollin dissolved effective March 1, 1856, at which time George Wylly moved his office a block to the east, entertaining a brief partnership with Thomas Collins before buying him out in March of 1858. Now occupying the “SE corner of Drayton and Bull Lane,” (“e” on the Derby Ward graphic) Wylly was located just across the lane from the offices of another brokerage, owned by C.A.L. Lamar (“f”). Lamar, in 1858, was the secret owner of a certain racing yacht by the name of the Wanderer, a vessel which would achieve infamy by the end of the year. Wylly’s former partner, John Montmollin was co-owner of the Wanderer. With the dissolution of his partnership with Wylly in 1856, Montmollin maintained an office on “Bull St. opposite Pulaski House,” (“b” on the graphic) and opened in 1856 an enormous storehouse next to the brokerage of David Dillon, where he advertised corn, wheat and slaves “at Montmollin’s Building, west side of Market Square.”

Below are some examples of Montmollin’s advertisements; private sales were handled within his properties while public sales were conducted at the stands by the court house:

Montmollin was a vocal proponent of reopening the Atlantic Trade, an idea by the 1850s gaining political traction in certain circles. In the last weeks of 1858, hushed rumors began spreading around town.

In October of 1858 the Wanderer left the coast of West Africa with human cargo aboard and authorities in pursuit. It swiftly outran its pursuers, landing on Jekyll Island on November 28 with more than 400 Africans—the last major slave ship to reach the shores of this country. Between December 1 and December 3 its cargo of men and women was dispersed among several smaller vessels and tugs and fanned out in multiple directions; C.A.L. Lamar employed his own tugboat, the Lamar, to ferry a group up the Savannah River. It crept past town in the dark of night December 3 and landed its captives at a dark water crossing some fourteen miles upriver from Savannah… by the South Carolina plantation of one John S. Montmollin.

“If Africans are to be imported, we hope in Heaven that no more will be landed on the shores of Georgia,” remarked the Savannah Republican in the months that followed. The extent of John Montmollin’s role in the Wanderer remained mostly unrecognized during his lifetime; in April of 1859 a federal court grand jury declined to indict him on the charge of “holding African negroes” at his plantation. Only months later he came to a grisly end; killed in June of 1859 at the age of 51 in a boiler explosion on a steamship while conducting business on the river. From the June 11, 1859 Morning News:

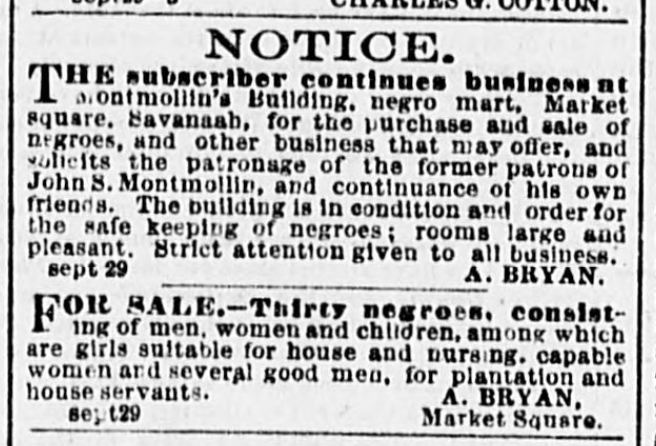

With the death of one commission broker, however, another simply took his place. Alexander Bryan leased the old Montmollin storehouse in Decker Ward and continued offering slaves as “A. Bryan’s Negro Mart” without missing a beat. In September, 1859 the following advertisement appeared:

The property still stands today. The story of the Montmollin/Bryan warehouse would go on to become one of the most fascinating in Savannah’s history as the Civil War drew to its closing days; its thread may be picked up in a companion post on this blog.

The William Wright “Slave Yard”

Like satellites revolving around a common star, Wylly, Montmollin, Bryan, Dillon and Lamar all seem to have relied on—and maintained their offices around—the Wright slave yard (“c” on the graphic). Maintaining a large holding pen on Bryan Street, by 1858 the Wright slave yard had grown into a behemoth of a property, occupying an entire 60 x 90 foot lot in Derby Ward.

From the December 9, 1858 Savannah Morning News:

The establishment that Joseph Bryan took over was extensive. One finds it listed in the newspapers variously as “near Monument Square,” and “next to Merchants’ & Planters’ Bank,” while the 1860 City Directory lists its location on “Bryan opp. Johnson square.” The sobering fact is that this “negro yard” begun by William Wright a few years before faced Johnson Square.

Perhaps the most active of the slave brokers during the 1850s, Wright’s announcements advertising his current offerings were a longtime daily feature in the Morning News. Wright obtained the 30 x 90 foot western half of Jekyll Tything Lot 8 of Derby Ward in 1853, inclusive on the site was an old frame house, circa 1830 and visible in Cerveau’s 1837 painting, “A View of Savannah”.

The 1853 map of Savannah by Edward Vincent depicts the half lot of No. 8 that Wright purchased that year, which I have marked in red.

Two years later Wright purchased the entire neighboring Lot 7 from Samuel Dayton on November 1, 1855. Wright quickly sold the western half of Lot 7 to the Merchants & Planters Bank, but he maintained his “eastern 7/western 8 combo” as a slave yard and holding pen, encompassing both the orange and red squares.

Though no physical trace of Wright’s establishment still exists today, to give its location some context, the Wright/Bryan property occupied today’s 14 to 22 East Bryan.

“William Wright, now owning all of lot 7 and part of lot 8, enclosed the area and used it as a Negro holding yard. The property had a wooden frame building standing on the premises. On December 1, 1858, Wright sold the above property including the frame house extending from the east side of the Merchants and Planters Bank building to Joseph Bryan.”

– C. Berry, “Site of the European House,” Demolished Buildings notebook, coll. #1320, GHS

Joseph Bryan’s previous place of business had been at J. Bryan & Son, 117 Bay Street (old address system), a location he first advertised from in November, 1852, a lease within the Central Railroad Bank building (“h” on the Derby Ward graphic). While one does find in the newspapers slave sales advertised from his 117 Bay Street location, it was with the purchase of William Wright’s slave yard that Joseph Bryan entered the big leagues. In the category of wasting no time, the same day he advertised his purchase of the Wright property Bryan also posted the following three ads in a row:

Not long after his 1858 retirement William Wright died in 1860, and in an estate sale on the first Tuesday of March, 1861 Wright’s remaining properties were auctioned off on the very same court house steps where he had sold so many other lives away.

Joseph Bryan, in the meantime, continued his business in the yard north of Johnson Square until 1863.

It is not hyperbole to claim that Joseph Bryan probably sold more enslaved persons than any other individual broker in 19th century Savannah. His fortunes peaked in 1859 as he took consignment of the Great Slave Auction of the Butler plantations (also known as the Weeping Time), whose saga we’ll examine momentarily. But even fortune fades to mortality, and “after a long illness” (Morning News, December 7, 1863), Bryan died in December of 1863. His widow leased the old slave yard property to A. H. Sadler and James Hines, who reopened the yard one more time in July of 1864.

Below is an image of Bryan Street, looking north from Johnson Square, circa 1865, which happens to capture a glimpse of the old site. The three-story structure at the forefront of the image was the aforementioned 1856 Merchants & Planters Bank building, which by 1865 was serving as the headquarters for the provost marshal (the blurry object at the center of the image seems to be an American flag being waved from the individuals in the second floor window). It is to the right of that building that I will draw the readers’ attention.

The office of the provost marshal was advertised within the newspapers on “Bryan street, three doors from Bull street.” In the 1857 “A Card” advertisement pictured above Wright described his own office as the “first door east of the Merchants’ and Planters’ Bank,” syncing up the geography and making his the fourth door from Bull Street. The Wright/Bryan office in question appears to have been a modest one-story brick building, adjoined to the east by a large and featureless wall with a heavy door. To be blunt, one would not find any advertisements encouraging a visit to the fifth door from Bull Street. If my interpretation of the image is correct, there was no visibility into the premises from the square, nor vice versa. The pen was behind the wall with the door (see detail below).

Nearly a decade after the Civil War, on November 2, 1874, Jane Bryan sold the former slave yard property to one John Ryan. The site remained virtually in-tact as late as 1881, when Daniel Purse purchased the property “to the east end of the wooden frame building now standing on the premises.” (GHS coll. #1320) Soon thereafter he demolished the old 1830 frame dwelling depicted in Cerveau’s painting and the office & wall depicted in the 1865 image, erecting instead a new brick range running the full length of the eastern 7/western 8 combo. The 1884 Sanborn Map finds the old slave yard site gone.

The Stevenson mart (“d” on the Derby Ward graphic) was on the same block of Bryan Street as the Wright/Bryan slave yard. Short-lived though it may have been, surprisingly, a small portion of the building appears to still exist today.

“The undersigned will open on the 1st January next, a mart for the reception and sale at Auction of Negro property.

J. A. Stevenson”

– Savannah Morning News, December 3, 1862

From January 1, 1863 to the end of 1864, J. A. Stevenson ran a slave mart just a few additional doors down from the old slave yard, in a property at 108 Bryan Street (old style), or today’s 34 East Bryan Street. Promoting “Negroes for sale privately at my mart,” (Morning News, March 17, 1863)

Not even the waning days of the Civil War broke his stride; Stevenson evidently joined the Confederate army—a September 12, 1864 Morning News mentions “Col. J. A. Stevenson’s command” near Atlanta—and left the business in the hands of his associate, J. Kesterson.

“Lot of Prime Negroes for sale at J.A. Stevenson’s, No. 198 Bryan street.

J.G. Kesterson, Agent”

-Savannah Morning News, October 17, 1864

A mere nine weeks later, the Union Army was in Savannah. The 1867 City Directory finds Col. Stevenson back in Savannah and operating a more traditional commission brokerage, sans slaves, at 190 Bay Street (old style), leaving his old leased slave house to other tenants. In 1896 the Citizens’ Bank building was erected on the site; all that survives today of the former building is an exterior stairwell and remnants of a western property wall, now the east wall of 32 East Bryan; the stairs are between the buildings. Depicted in the 1884 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map illustration above, the staircase afforded egress to the basement.

Enslaved persons brought to Savannah for sale were often temporarily housed in the commercial brokerage houses sponsoring the auction, or the oversized Wright slave yard… or possibly beneath the Pulaski House Hotel on Johnson Square. In 1958, workmen demolishing the old hotel building were startled to discover the sub-grade basement. It was speculated that this was where guests to the hotel might keep their slaves, a theory seemingly confirmed by this undated account by a former slave named George Carter.

“There was a pen under the Pulaski House where they lock up [slaves] whenever they got there in the night, and the man what have them in charge done stop at the hotel. The regular jail weren’t for slaves, but there was a speculator jail at Habersham and Bryan Street. They lock up the slaves in the speculator jail when they brought them here to the auction. Most of the speculators come in the night before the sale and stop at the Pulaski House. The slaves was took to the pen under the hotel.”

– George Carter, undated

Carter referred to a jail at Habersham and Bryan; for the record, this author has never been able to find evidence of such a jail at this site. I might humbly suggest he might have meant instead Barnard and Bryan, the location of the aforementioned Montmollin/Bryan warehouse. As Alexander Bryan boasted of the property in his 1859 advertisements: “The building is in condition and order for the safe keeping of negroes.”

The Weeping Time

With 1859 came the fall of a titan. Following a massive reversal of fortune, Pierce Butler was forced to sell off his estate’s slaves in one of the largest slave auctions in history. And Joseph Bryan acted as its broker.

The enslaved populace could be viewed and inspected before the auction, and some may have even been held on the premises of Bryan’s slave yard on Johnson Square. As the advertisement below boasted, “The Negroes will be sold in families, and can be seen on the premises of Joseph Bryan in Savannah, three days prior to the day of sale, when catalogues will be furnished.”

The Daily Morning News may have printed the advertisements of the sale, but the newspaper does not appear to have covered the actual event. Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, however, another source quietly did.

In 1863 Fanny Kemble’s Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation was published. Written by the English actress (1809-1893) and former wife of Pierce Butler, whose marriage had crumbled under the strains of their two different worlds and her inability to reconcile the institution of slavery, the book was taken from her 1838-39 observations of plantation life on Butler Island and included glimpses of the population that would be sold off twenty years later. The Journal painted a grim picture—a real-life Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Its 1863 publication was followed the same year by the printing of a quasi-sequel, “What Became of the Slaves on a Georgia Plantation? Great Auction Sale of Slaves, at Savannah, Georgia, March 2d & 3d, 1859,” a 20-page expose pamphlet authored by Mortimer Neal Thomson (1832-1875). A journalist, Thomson attended the 1859 sale with his own agenda in mind, recording for publication the particulars of the event while posing as a potential buyer. As he claimed, “your correspondent was present at an early date; but… he did not placard his mission and claim his honors.”

“The office of Joesph Bryan, the Negro Broker, who had the management of the sale, was thronged every day by eager inquiries in search of information, and by some who were anxious to buy,” Thomson later reported. “For several days before the sale every hotel in Savannah was crowded with negro speculators from North and South Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana.” (Thomson, p. 3) Bryan was described by the correspondent as “a dapper little man, wearing spectacles and a yachting hat, sharp and sudden in his movements… as earnest in his language as he could be without actually swearing, though acting much as if he would like to swear a little at the critical moment.” (p. 10)

This sale in March of 1859 was an example of the unthinkable… one of the great Georgia sea-island “plantation societies” forced to sell off, piece-meal, the residents of its community. With 436 slaves listed to come onto the block, the proceedings were too large to be carried out in the isolation of Butler Island and even too large to be carried out in Savannah. The event was conducted at the Tenbroeck race track, three miles west of town, the only venue large enough to accommodate it. Constructed in 1856, the Tenbroeck Course held its maiden horse race in January, 1857; it also served as host for the annual fair of the Agricultural Club of Chatham and Effingham County, which lauded its “fine enclosure, halls, stables, &c., for the convenience of exhibitors and visitors.” (Republican, October 27, 1857) The event held here in March of 1859, however, was unique… it was referred to at the time as the “Great Sale,” and it’s true, there was nothing else to compare. Held on a dismal and enduring rain on Wednesday, March 2 and Thursday, March 3, 1859, the Great Sale was better remembered by history and by those who endured it as “the Weeping Time.” None had ever been sold before.

“Some of them [those to be auctioned] regarded the sale with perfect indifference, never making a motion, save to turn from one side to the other at the word of the dapper Mr. Bryan, that all the crowd might have a fair view of their proportions, and then, when the sale was accomplished, stepped down from the block without caring to cast even a look at the buyer, who now held all their happiness in his hands. Others, again, strained their eyes with eager glances from one buyer to another as the bidding went on, trying with earnest attention to follow the rapid voice of the auctioneer. Sometimes, two persons only would be bidding for the same chattel, all the others having resigned the contest, and then the poor creature on the block, conceiving an instantaneous preference for one of the buyers over the other, would regard the rivalry with the intensest interest, the expression of his face changing with every bid, settling into a half smile of joy if the favorite buyer persevered unto the end and secured the property, and settling down into a look of hopeless despair if the other won the victory.”

– Mortimer Thomson, 1863

As Thomson explained: “The negroes came from two plantations,” owned by Butler, “one a rice plantation near Darien… the other a cotton plantation on the extreme northern point of St. Simon’s.” Thomson remarked that the men, women and children were “brought to Savannah in small lots… the last of them reaching the city the Friday before the sale.” Most, upon arrival, “were taken to the Race-course, and there quartered in the sheds erected for the accommodation of the horses and carriages,” where they were “huddled together on the floor, there being no bench or table.” (p. 4-7) The auction premises were partly sheltered from the rain; “the [auction] room was about a hundred feet long by twenty wide,” and “open to the air on one side, commanding a view of the entire Course. A small platform was raised about two feet and a-half high, on which were placed the desks of the entry clerks, leaving room in front of them for the auctioneer and the goods.” (p. 10)

In addition to describing the surroundings, Thomson’s pamphlet attempted to chisel a human face on the tragedy. Included in his narrative were various episodes of those who were to be sold, including the story of Jeffrey—chattel No. 319, and Dorcas—chattel No. 278, who “had told their loves, and exchanged their simple vows, and were betrothed.” [Editor’s note: I have cleaned up Thomson’s inflections of Jeffrey’s speech that have not aged well]

“Jeffrey, chattle No. 319, marked as a ‘prime cotton hand,’ aged 23 years, was put up. Jeffrey being a likely lad, the competition was high. The first bid was $1000, and he was finally sold for $1310. Jeffrey was sold alone; he had no incumbrance in the shape of an aged father or mother, who must necessarily be sold with him; nor had he any children, for Jeffrey was not married. But Jeffrey, chattle No. 319, being human in his affections, had dared to cherish a love for Dorcas, chattle No. 278; and Dorcas, not having the fear of her master before her eyes, had given her heart to Jeffrey. Whether what followed was a just retribution on Jeffrey and Dorcas, for daring to take such liberties with their master’s property as to exchange hearts, or whether it only goes to prove that with black as with white the saying holds, that ‘the course of true love never did run smooth,’ cannot now be told. Certain it is that these two lovers were not to realize the consummation of their hopes in happy wedlock. Jeffrey and Dorcas had told their loves, had exchanged their simple vows, and were betrothed to each other as clear, and each by the other as fondly beloved as their skins had been a fairer color….

“Be that as it may, Jeffrey was sold. He finds out his new master, and, hat in hand, the big tears standing in his eyes, and his voice trembling with emotion, he stands before that master and tells his simple story, praying that his betrothed may be bought with him. Though his voice trembles, there is no embarrassment in his manner, his fears have killed all the bashfulness that would naturally attend such a recital to a stranger, and before unsympathizing witnesses; he feels that he is pleading for the happiness of her he loves, as well as for his own, and his tale is told in a frank and manly way.

“‘I love Dorcas, young Master; I love her well and true; she says she loves me, and I know she does; the good Lord knows I love her better than I love any one in the wide world—never can love another woman half so well. Please buy Dorcas, Master. We’ll be good servants to you long as we live. We’re to be married right soon, young Master, and the children will be healthy and strong, Master, and they’ll be good servants, too. Please buy Dorcas, young Master. We love each other a heap—do, really true, Master.’

“Jeffrey then remembers that no loves and hopes of his are to enter into the bargain at all, but in the earnestness of his love he has forgotten to base his plea on other ground till now, when he bethinks him and continues, with his voice not trembling now, save with eagerness to prove how worthy of many dollars is the maiden of his heart.

“‘Young Master, Dorcas prime woman—A woman, sir. Tall gal, sir, long arms, strong, healthy, and can do a heap of work in a day. She is one of the best rice hands on the whole plantation, worth $1200 easy, Master, and a first rate bargain at that.”

“The man seems touched by Jeffrey’s last remarks, and bids him fetch out his ‘gal, and let’s see what she looks like.”

“Jeffrey goes into the long room, and presently returns with Dorcas, looking very sad and self-possessed, without a particle of embarrassment at the trying position in which she is placed. She makes the accustomed curtsy, and stands meekly with her hands clasped across her bosom, waiting the result. The buyer regards her with a critical eye…. Then he goes to a more minute and careful examination of her working abilities. He turns her around, makes her stoop, and walk; and then he takes off her turban to look at her head that no wound or disease be concealed by the gay hankerchief; he looks at her teeth, and feels of her arms, and at last announces himself pleased with the result of his observations, whereat Jeffrey, who has stood near, trembling with eager hope, is overjoyed, and he smiles for the first time. The buyer then crowns Jeffry’s happiness by making a promise that he will buy her, if the price isn’t run up too high. And the two lovers congratulate each other on their good fortune.…

“At last comes the trying moment, and Dorcas steps up on the stand.

“But now a most unexpected feature in the drama is for the first time unmasked: Dorcas is not to be sold alone, but with a family of four others. Full of dismay, Jeffrey looks to his master, who shakes his head, for, although he might be induced to buy Dorcas alone, he has no use for the rest of the family. Jeffrey reads his doom in his mater’s look, and turns away, the tears streaming down his honest face.

“So Dorcas is sold, and her toiling life is to be spent in the cotton fields of South Carolina, while Jeffrey goes to the rice plantation of the Great Swamp….

“In another hour… I see Jeffrey, who goes to his new master, pulls off his hat and says: ‘I’m very much obliged, Master to you for trying to help me. I know you would have done it if you could—thank you, Master—thank you—but—it’s—very—hard’ – and here the poor fellow breaks down entirely and walks away, covering his face with his battered hat, and sobbing like a very child.”

– Thomson, p. 16-18

The total proceeds for the Butler family estate sale brought in $303,850 for 429 men, women and children. In a somewhat surreal parting scene, Thomson recorded a throng of Butler’s former slaves gathering around their former owner as he bade them farewell and gave each one the parting gift of a silver dollar. As Thomson remarked: “To every negro he had sold, who presented his claim for the paltry pittance, he gave the munificent stipend of one whole dollar.”

“That night, not a steamer left that Southern port, not a train of cars sped away from that cruel city, that did not bear each its own sad burden of those unhappy ones, whose only crime is that they are not strong and wise. Some of them maimed and wounded, some scarred and gashed, by accident, or by the hand of ruthless drivers—all sad and sorrowful as human hearts can be.”

– p. 20